George Beahan Daly, second son of John Daly and Elizabeth (Beahan) Daly, was born on September 30, 1852. Michigan was then a pioneer state, and the family lived on a farm two miles southeast of the town of Flint. The city of Flint has long since spread out over that farm site.

His father John Daly had come from County Meath, Ireland about fourteen years before with his parents, brothers, and sisters, and had settled near Mount Morris. The wife Elizabeth‘s family had come a year or two earlier from Seneca County, New York State. Her sister Mary, Mrs. Andrew McDowell, came to live in Flushing County. She told her grandchildren about coming to Michigan. It was 1845 and they traveled by train to Pontiac, then to Flint by covered wagon. Their home was a log cabin without windows. She helped her husband with all the work so he could clear the land for farming. The oldest of the two small children, Jane, was walking, and when Mary milked the cows, with a smudge burning to keep the mosquitoes away, she had to tie Jane to the bedpost to keep her out of the fire.

In the fall of 1856 John took his family to Clark County, Missouri, to a town called Santa Fe, but later re-named St. Mary. By then the family consisted of Linus, George, Florence, and Julia (the baby). John ran a grocery store with a man named Elwood who talked a lot against slavery and one morning was found hanged in his own orchard.

After this tragedy the Dalys moved down the river and across to the Illinois side and started a woodyard. There were many steamboats carrying immigrants from the old country up into the Mississippi valley to make new homes. These boats used wood for fuel and as they could carry only a day’s supply there had to be many woodyards along the river. The wood was cut in four foot lengths and piled eight feet high and long enough so there were twenty cords to a pile if honestly piled. This was the country where Mark Twain lived and here is a paragraph from Huckleberry Finn which well describes the scene and life there at that time: “Then we set down – and watched the daylight come. The first thing to see looking away over the water, was a kind of dull line – that was the woods on the other side – you couldn’t make anything else out; then a pale place in the sky; then more paleness, spreading around – and the east reddens up, and the river, and you make out a log cabin in the edge of the woods, away on the bank on t’other side of the river, being a woodyard, likely, and piled by them cheats so you can throw a dog thru it anywhere.”

This was before the railroads took away the business from the steamboats. George never forgot the thrill of hearing the steamboat coming and in later life he often mentioned his life on the Mississippi when he heard the steamboat whistle that the trains used. It must have been hard for those boys, living in such a lonely place, to see those boats going by and never get to ride on them.

During the election campaign of 1860 when George was eight years old, he heard people say that if Lincoln were elected it would mean there would be war; later when he heard that Lincoln was elected he went out behind the woodpile and cried.

They ran their wood yard through the later years of the Civil War and used to see hospital ships pass, carrying wounded soldiers. These ships were painted red and were never fired upon. Once one landed near their woodyard and the crew buried a Southern soldier who had died on the boat.

George V. Beahan, for whom George Daly was named, had planned to send George to school, and had put money for that purpose in a bank in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The bank failed, and the money was lost. In February 1865 George V. Beahan was killed in a logging accident. His family decided to carry out his wishes in regard to George Daly’s education, so George came back, alone, that summer, to Michigan. He was thirteen years old. In December of the same summer, George’s mother died in Lima, Illinois, and the rest of the family came back to Flint with the three more boys, John, Edward, and Austin, who had been born in Missouri.

George stayed at the home of the grandmother, Polly Beahan, and walked to school in Flint, a distance of several miles. At that time the approved way of becoming a lawyer was to go into the office of a lawyer and “read” law. So after high school, George went into the office of George Durand, who was mayor of Flint and Congressman and finally Judge of the Supreme Court.

George taught school in the winter and studied law in the summer. He was admitted to the bar in the state of Michigan at the age of twenty, and practiced law there for about six years. He walked for recreation, and one summer he and a companion made a walking tour of part of Michigan–sometimes sleeping in the open and working a little on farms here and there.

Once after George Beahan’s death his mother invited George Daly to select something from George Beahan’s possessions for his own. George chose the walnut book case and used it the rest of his life. After his death his oldest son, Alex, took it to his home and in 1944 it was burned when the house burned down. It had a row of “pigeon holes” across the top of the desk, and here many interesting old letters were preserved, and they were not in it when it burned.

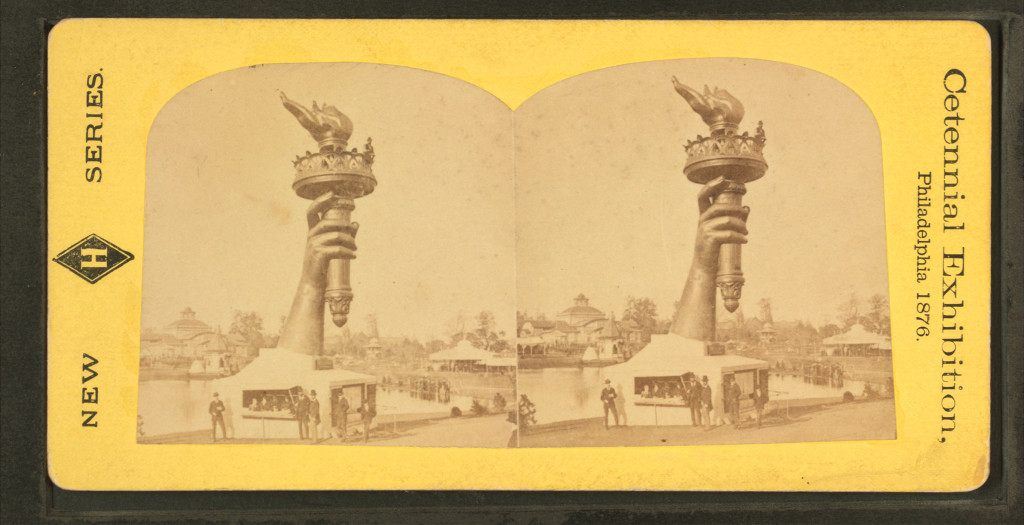

In October 1876 George went to the Centennial and to see New York. He told in a letter of going through Watkins Glen, New York, and stopping to see a cousin, Thomas Beahan, that he had known in Michigan. They went to call on the Hugh Carney family and stayed to supper and visited so long he missed his train and had to take the train the next morning. He was glad of the chance to get acquainted with his cousins and also to ride through Pennsylvania in the daytime. Fifty years afterwards the main things he remembered were the two little dark-eyed Carney girls.

In 1880 at the age of 27, George and his brother John came to Dakota with J.D. Lavin and others. They came to Watertown by train. As that was the end of the line, they bought a team and a light wagon and drove to Columbia. There they selected their claims and drove to Jamestown, the end of the Northern Pacific Railroad. There they took the train to Fargo, where the land office was located, and filed on their land.

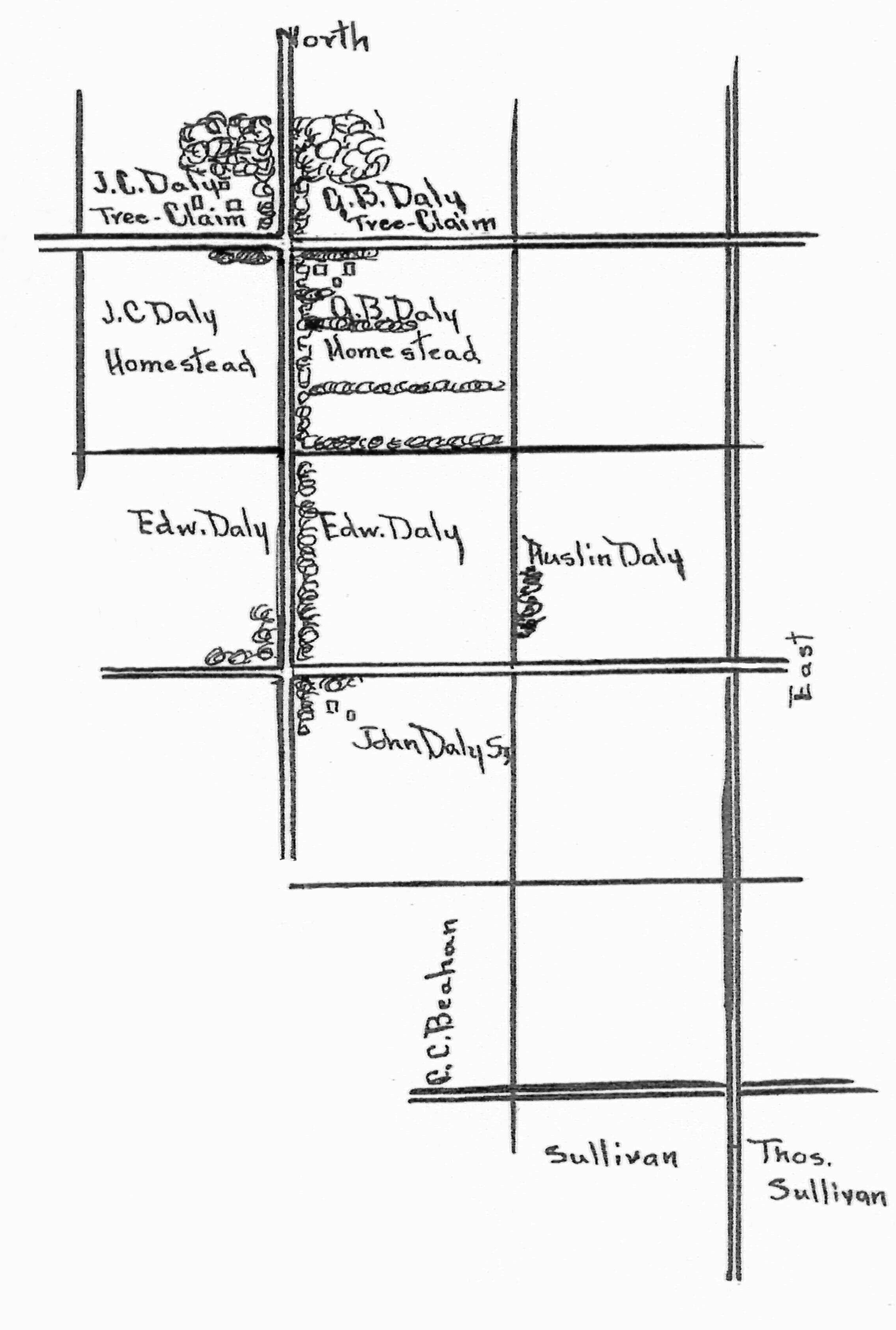

George took his preemption quarter one mile north and one mile east of Columbia. Later the same year their father, John, and brothers, Eddie and Austin, came to take land and in order to get adjoining land they had to go seven miles northeast of town. That are a is now known as Daly Corners.

An old diary with the first entry “March 20, 1880: Card gave me this diary today,” was a parting gift when George was leaving Michigan. Entries through the same spring tell of planting potatoes, beans, and corn, and of working for a neighbor at building a sod house. The June 15th is “Worked first day on my sod house,” and on June 28th “Father Haire came.” In July he mentions his father and Austin hoeing and harrowing in the bagas.

That summer he and a man named Hemenger walked to Fargo. He wrote “Slept in the sandhills, or rather, tried to but couldn’t on account of the mosquitoes. Horrible night.” When they got to Fargo they went to work by the day at haying and harvesting; later at plowing and threshing. In October George was teaching school on the Cheyenne River. He mentioned gathering tree seeds and sending sacks of them to people in Columbia.

George brought into the county the first copy of territorial laws seen here, and it was he who drafted the petition for the organization of the county. Several letters from J.D. Lavin and Johnnie Daly tell of the fight to keep the county seat in Columbia and then of their great satisfaction when Columbia won the election. One of Lavin’s letters says “By unanimous vote of the county commissioners in session September 4th, 1880 you were appointed Probate Judge of Brown County to serve oil the next election.”

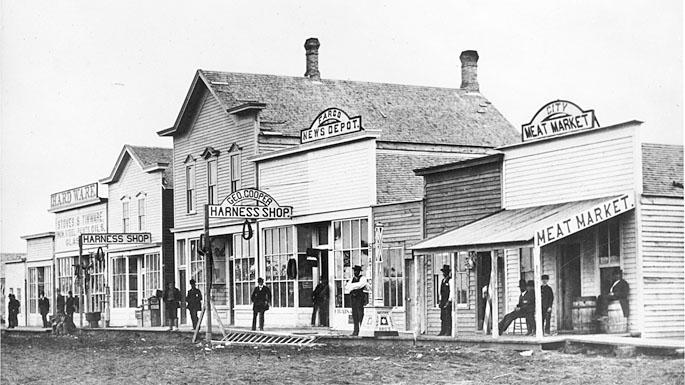

Columbia was growing fast, and her people had great hopes and plans for her future. People got quite excited over whether or not a power dam on the river would stop navigation. They hadn’t learned how the “Jim” could slow down and become only a series of small ponds for months at a time.

Johnnie wrote of the difficulty of hiring help to work with a team, hauling corn, etc. In one letter he says “I dug your potatoes and put them in your house. If it begins to get cold I will dig a hole in the house and put them in it.” Then he tells that Sullivan and Lynch had left some of their potatoes out and had them frozen. This was the Sullivan who was to be their father-in-law.

Another letter said “I brought two yoke 0f oxen, wagon, plow, and all picket rope belonging to them, of George Stevens for two hundred twenty-five dollars. I don’t know what you will think but I thought I couldn’t better it. He was offered one hundred and twenty-five for one yoke of them. The other yoke are younger and smaller, about like Elliot’s oxen.” Then he tells of giving up his trip to Michigan to save the sixty dollar train fare and also to be on his claim so it wouldn’t be “jumped.” He planned to dig a well and to put a partition in the sod house so he could keep the oxen in one end of it. This was a common practice in those days so a man would be in no danger of getting lost while going to care for stock. There were no fences or trees for landmarks. He ended the letter: “Won’t I have a lonesome old time? Send me all the papers you can get ahold of.”

This plan all seems to have changed as a letter from Lavin a little later states that Johnnie left for Flint shortly after election. Then a letter headed “Marshall, Minnesota March 27th” tells that Johnnie and John Meenan and Kanaly started out with their oxen but have come back. He says “This is the best place to wait for the snow to go off–have plenty of everything here to eat. I think the farther west you go the scarcer you find provisions.” Then he warns George to bring along provisions, in case he gets to the claim first.

George’s diary entry for May 24th is: “Got home about 3 o’clock.” Through the rest of the month the entries are of planting trees, potatoes, onions, wheat, and corn.

He taught the first school in Columbia which was probably the years 1882 and 1883. The school was on the hill east of Columbia where the Catholic cemetery is now and there many of these pioneers are now buried: Fr. Haire, the Kanaleys, Sullivans, Murphys, George and Johnnie Daly, their father, and many others.

The summer of 1883 the Sullivans came back from Michigan and stayed with the Dalys till they had their own frame house built. That summer the Dalys moved to their own permanent homes and the next February Johnnie married Minnie Sullivan and the next September George married her sister Hannah. The two couples lived side by side till about 1906 when Johnnie and Minnie moved to Aberdeen and turned the farming over to their boys. George and Hannah lived in this home the rest of their lives and here raised their thirteen children. Through the years they turned the bare prairie to a grove of trees and had nearly every variety of tree that will grow in the northern climate. The evergreens of six or seven kinds were a landmark for the county for years. It was the only large number of them in many miles. All the Daly claims had large groves and they joined in one continuous grove, making this a center for picnics and social affairs and a meeting place for discussion of politics and farm problems.

George was among the first to try new, drought-resistant shrubs and crops. They got a hive of bees and Hannah enjoyed working with them. She often had honey to sell and give to people. Usually she had a dozen or more hives in operation the rest of her life.

Through the first years of poor crops or complete failures many friends and neighbors gave up and went back east. It was probably because the Dalys lived near together and shared work and tools that they survived the bad years. Among George’s old papers was the beginning of a poem:

In the first legislature of South Dakota in 1891, and again in 1897, George was a representative. A friend of his, Herbert Cronin, said of him: “He was a politician in the best sense of the word, not merely to secure office but to advance the ideas and reforms which he believed to the advantage of all.”

A strong believer in cooperation, he helped organize the Groton Ferney Telephone Company, the Brown County Mutual Insurance Company, Columbia’s Farmer’s Elevator, and the Tacoma Park Association (of which he was president for thirteen years). This latter was not only for a pleasure resort but as a center for the discussion on social and political reform. Here they had a chautauqua for a week, each year. People came from all over the county and camped here for a week. There were lectures by such celebrities as W.J. Bryan, Hobson, Carrie Nation, and Robert LaFollette. There were ball games and at night there were plays put on by the stock company that was encamped there. That one week was the high spot of the year for hundreds of young people. The Dalys nearly always camped, even when there was a small baby.

About the year 1905 George bought the Pioneer Sentinel, a weekly newspaper in Aberdeen, changed the name to the Aberdeen Democrat and edited it for several years, staying in town through the week and going home weekends. His son Francis worked with him for a year or two. Searle Brothers finally bought the paper and George went back to the farm. Shortly after that he began teaching the home school. A great reader, he saw to it that his family were always well supplied with worthwhile reading material and while he ran the paper, he would bring home books from the library. He read many books aloud to the family in the evenings. He liked poetry and wrote poems. Some were published in Pasque Petals and in Braithwaite’s Anthology of American Poetry. The last years of his life he was telling, in poetry, the story of the pioneering of his great-grandparents, George and Polly Faussett. His eyesight failed him and he never finished it.

September 26, 1932 Hannah wrote: “Our radio is working good now. Papa watches for the news every day. He can’t see to read so has to get the news mostly from the radio. I read the papers to him but he gets more satisfaction with the radio. We sat up almost all night the night of the Democrat convention.”

Hannah died of a heart ailment November 7th, 1932. George lived on with his son Dick at the home place. He always liked to walk. In January he caught a cold and decided to “walk it off.” He called on a neighbor a half mile away, but the cold got worse and developed into pneumonia. The family took him to the hospital in Britton, but his condition became worse and on January 18th, 1933 he passed away.