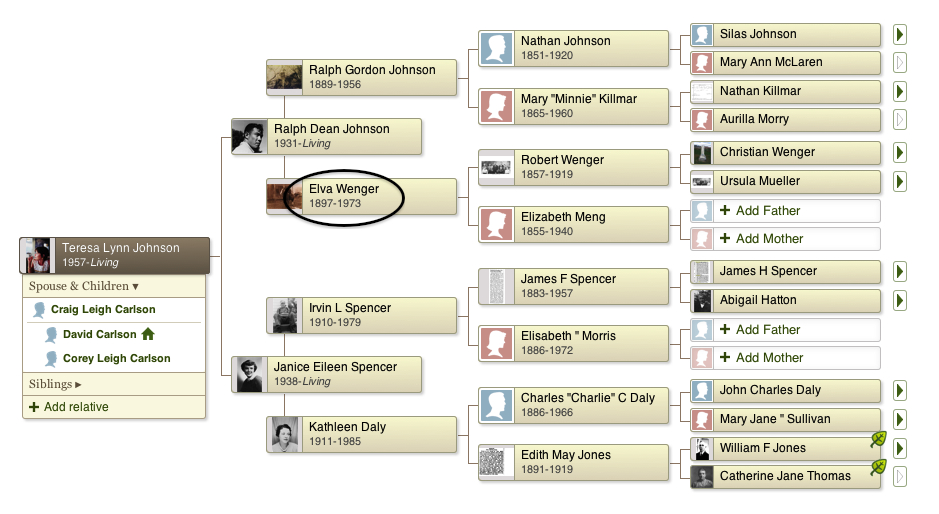

Elva Wenger was born on September 15, 1897 in Wisconsin to Robert Wenger and Elizabeth (Meng) Wenger. She was married to Ralph Gordon Johnson. They had six children: Robert (b. 1918), Clare (b. 1921), Joseph (b. 1923), Ruth (b. 1927), Ralph Dean (b. 1931), and Mary (b. 1935). Her son Ralph remembers her wearing a housedress and black lace-up shoes with a heel.

A biography of Elva written when she was 66:

“The name Elva Johnson is unfamiliar to the world in general. She has had no worlds to conquer and nothing to prove. Her life is her own, but she will be remembered. At sixty-six years of age, she is full of joy and compassion, and to her life is still an adventure. The reason for her contentment does not stem from deep religious convictions; it does not arrive after repeated reminiscent wanderings through the past. She is not constantly seeking attention, nor is she basking in the dawning light of old age. She is a vital force and one to be reckoned with. She was born with a sense of humor that has been neither dulled nor distorted by time, and through it she encompasses life and outwits her adversaries.

Elva is not exactly the prototype for another “Whistler’s Mother;” her husky voice and large frame seldom recede into the background, and she expresses her opinion profoundly. In her voice there is laughter, and in her eyes there is a roguish gleam. She loves people and her own cooking; her favorite indulgence is a glass of blackberry brandy, which she can drink with the dispatch of an Indian going to hunt.

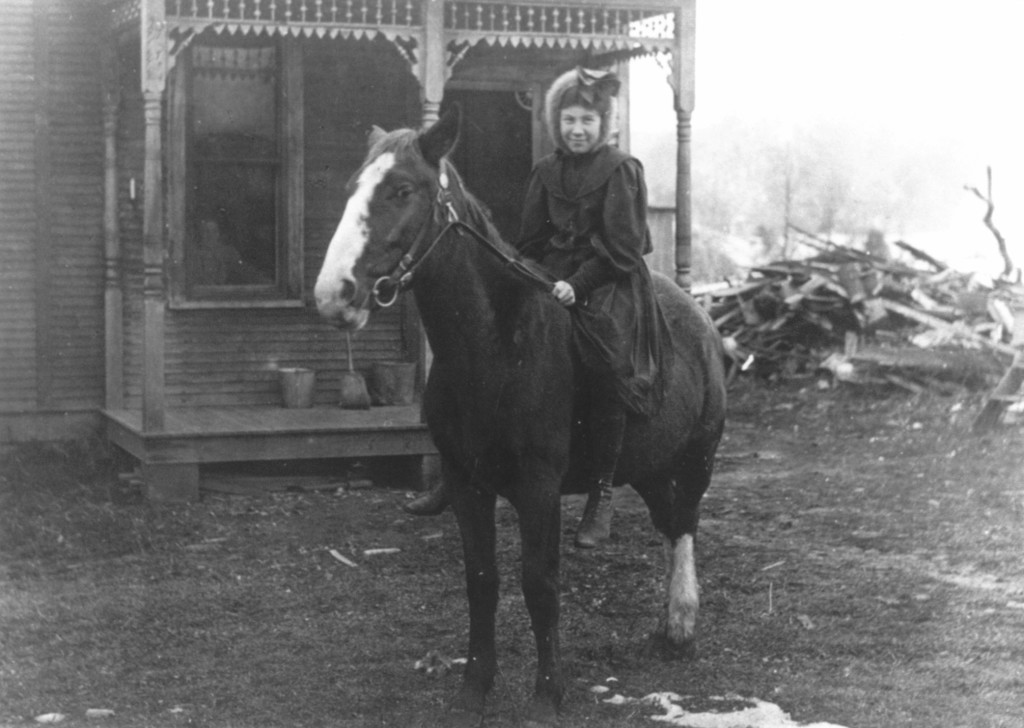

She was born on the fifteenth of September in 1897 to Robert and Elizabeth Wenger in the small town of Alma, Wisconsin. The youngest of six girls, she was raised on a dairy farm, six miles from town, on the banks of the Mississippi River. The lights of the river boats furnish a descriptive background for Elva’s childhood. Her father, Robert Wenger, was also born in Alma; but her mother, Elizabeth, was born in Switzerland and came to America with her family when she was just six weeks old.

In 1897 and during the following years, Wisconsin was getting a head start in becoming America’s leading dairy state, and the Wenger family did their share in helping the dairy business along. With no boys in the family, the six girls followed their father in taking care of the farm and the thirty cows. “We really had to work,“ Elva relates. “We girls milked all those cows and had to put out all the feed. The milking back there was from March to October, and in the summertime there was the haying.”

Elva and her sisters were a happy, healthy bunch. They needed to be hardy to get through the cold Wisconsin winters on their feet, for they walked two miles to school all winter long. The school that taught the Wenger girls their ABC’s consisted of a one-room building that included eight grades. Eventually a new school was built with two rooms and four grades to each room.

The Wengers’ main social outlet was through their church, which was only a quarter of a mile away; it was the gathering place for the youngsters all summer. There they spent a good part of every Sunday, they met the neighbors, and they had church socials. The denomination of the church was the Reformed Lutheran, and dancing was not allowed. This made it necessary for the girls to attend the dances a little farther away from their home. Elva’s father would take all the girls to the dance on Saturday night and would wait for them. He was a kind, patient man, for many times the dance didn’t end until five in the morning. When they would all reach home at daybreak, there would still be the chores to do, and half of the girls would milk while the other half took a nap in the hay loft. Then there was always church right after the noon meal, and six girls desperately trying to stay awake through the long sermon. “I suppose we didn’t know any better, you know,“ Elva remembers, “but we really enjoyed life. We never knew we were missing anything. We got to town about once or twice a year; of course it was with a horse and buggy. Oh, I remember that was a real treat when we would get to go to town.”

Everybody was welcome at the Wenger farm. All of the cousins and relatives would come from town and stay all night whenever they could get away. A bachelor neighbor lived close by, and he was welcome too. In the winter he would take all the girls and the cousins to another country dance fifteen miles away, in Praag, Wisconsin. The oldest Wenger girl had married and was living in Praag, so the country dance held there was included in the social life of those in Alma. The bobsled would be hooked up and everyone would pile into it for the wild, two-hour ride over the steep bluffs and into Praag. Elva’s sister would have a houseful of tired young dancers before the night was over.

The Wengers also had a cheese factory on their farm. A fresh batch of cheese was made night and morning from the milk brought in by the surrounding neighbors. But even in those early years the big companies were making claims on the resources of the farmers, and in the mid-1900s the neighborhood cheese factory was replaced by a large company installation.

As time progressed the older girls got married and moved to town. Elva’s mother and father finally sold the farm and moved to town also. Elva was the last girl left at home. At nineteen she went to Columbia, South Dakota, to live with her sister Mary. She attended business college for a year and then worked in the local bank in Columbia. Shortly after she moved to Columbia she met Ralph Johnson at the evening church meeting. Thus began an enduring relationship that lasted for forty years. Ralph courted Elva for two years; then she married this dark, patient man, seven years her senior. He was the only man that she ever went out with.

Another small town, another small farm, but Elva wasn’t striving for fame. This time the town was a little larger, and the farm was a grain farm. The ten or twelve cows supplied the family with milk, but the main work came in planting and harvesting one thousand acres of grain. Two or three times a year, when she could get away, Elva would go back to Alma to visit her parents. They never left their little house in Alma, and her mother lived there twenty years after Robert died.

Up until the time when Elva moved to Columbia, she had never learned to cook. The family of girls was always too busy doing the outside work to pay much attention to what their mother was doing in the kitchen. All Elva knew how to make was pumpkin pie; but she had always wanted to cook. When she started living with her sister, she began to experiment. She learned in a hurry, and this art of cooking became one of her main interests and accomplishments. It is a blessing that she liked the kitchen so well, for during her life on the farm she cooked for the threshing crew every summer for six weeks, three meals a day.

The crew that moved onto the farm in those days for the threshing season were transients; all kinds of men from all parts of the country. Along with the professional tramps came the doctors, lawyers, and other educated men. Most of them were on the road, running from trouble or looking for more. Because this mixed crew lived on the farm, the Johnsons had a great many problems. The men would get drunk, fight among themselves, and go on shooting sprees. Some would steal. Dad Johnson (Ralph) found his best suit and dress shoes missing one Sunday morning. The culprit had walked away from the farm to avoid being traced.

Elva and Ralph Johnson had six children; all were born on the farm and delivered by an old country doctor. There were four boys and two girls. Their house was small, and the boys slept in one room and the girls in another. Again everyone helped with the work. There was the church, this time a Congregational one, and there were dances. School was closer to the farm, and so was the town. There was hunting and trapping all year long, and the country abounded with racoons, foxes, skunks, and muskrats. By the time the oldest boy was fifteen he had an old car. When they weren’t all trying to get the car to town, they were chasing foxes with it. Elva still hadn’t had time to tell if she was missing anything.

The advent of the second world war changed life for the Johnsons as it did for many other families. The boys left for the service, and without their help the Johnsons planted less and less. Soon the farm became too much for them to handle; and like Elva’s own parents, the Johnsons moved to town. They bought an old house in Columbia and remodeled it. The girls married local boys. After the war, when the boys came home, they found that much of their way of life had disappeared along with the battles and flag waving. There was little work to do at home, and there came a restlessness to these veterans that was known to so many others during this period. DUring the first summer they drifted from one thing to another. One venture they decided to go into was the painting business. With typical enthusiasm they bought a spray outfit and started painting the buildings on the local farms. On about the second job they painted the buildings, and the cows, and the chickens. That enterprise ended rather abruptly.

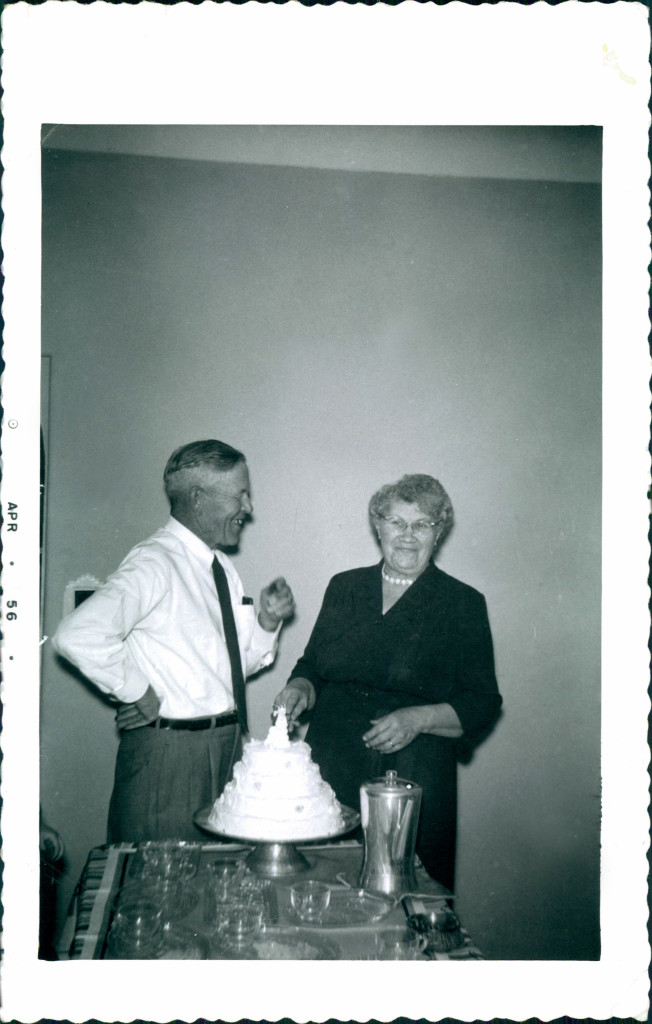

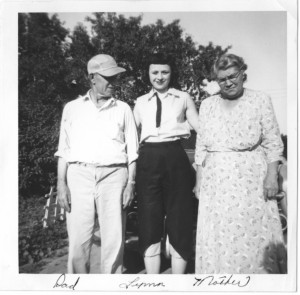

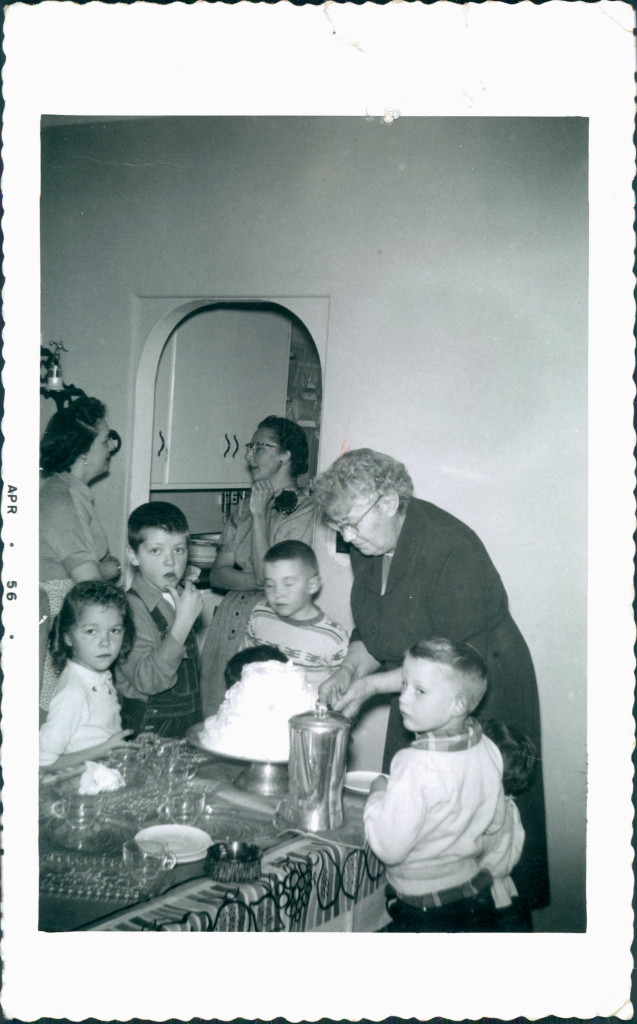

Elva At Mary’s Wedding

Ralph Johnson died of cancer in the fall of 1956. Elva continued to live in their home in Columbia, but she started traveling a little and would move in with her sons and daughters any time she could be of help. Today Elva still maintains her house in Columbia and returns to it several times a year. At present she is living in Bountiful (Utah) with her son Joe and his wife Yvonne. Joe teaches school and Yvonne nurses; Elva takes care of their four children. Early this summer she took the two youngest children with her on a visit to Columbia. They went by train and had breakfast in Butte (Montana). They saw everything there was to see and stayed in Columbia for six weeks. While Elva was in South Dakota, she had an offer of a job cooking on a Mississippi river boat. She has always wanted to work on the river, but she has never gotten around to it. Now she still has too much babysitting to do and too many cakes to bake for the family.

Elva Johnson has worked hard all her life. What she lacked in academic education she more than made up for in experience and personal accomplishment. She has had two main blessings during her long and productive life: a kind and patient father and a kind and patient husband. Through the love and understanding of these two men, she was able to realize her own worth; she became so busy that she didn’t know what she was missing. What was she missing?“

Elva died of a heart attack on February 14, 1973 in Aberdeen, South Dakota. She was preceded in death by two of her daughters and her husband.