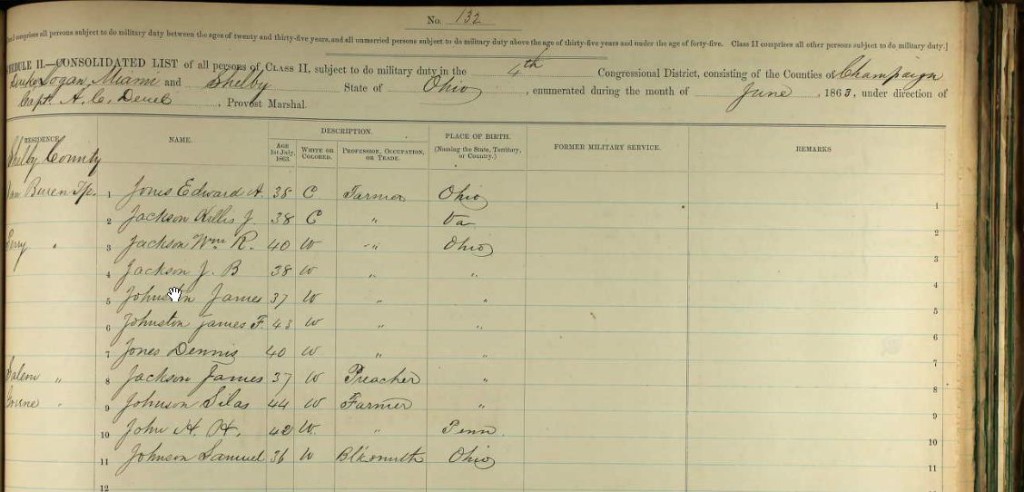

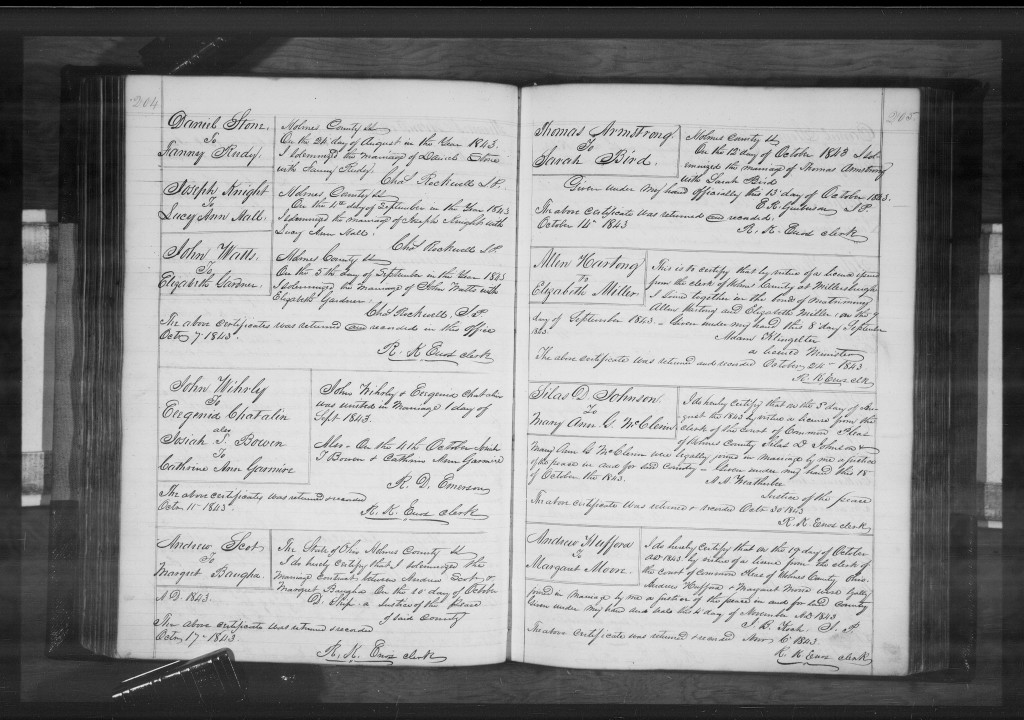

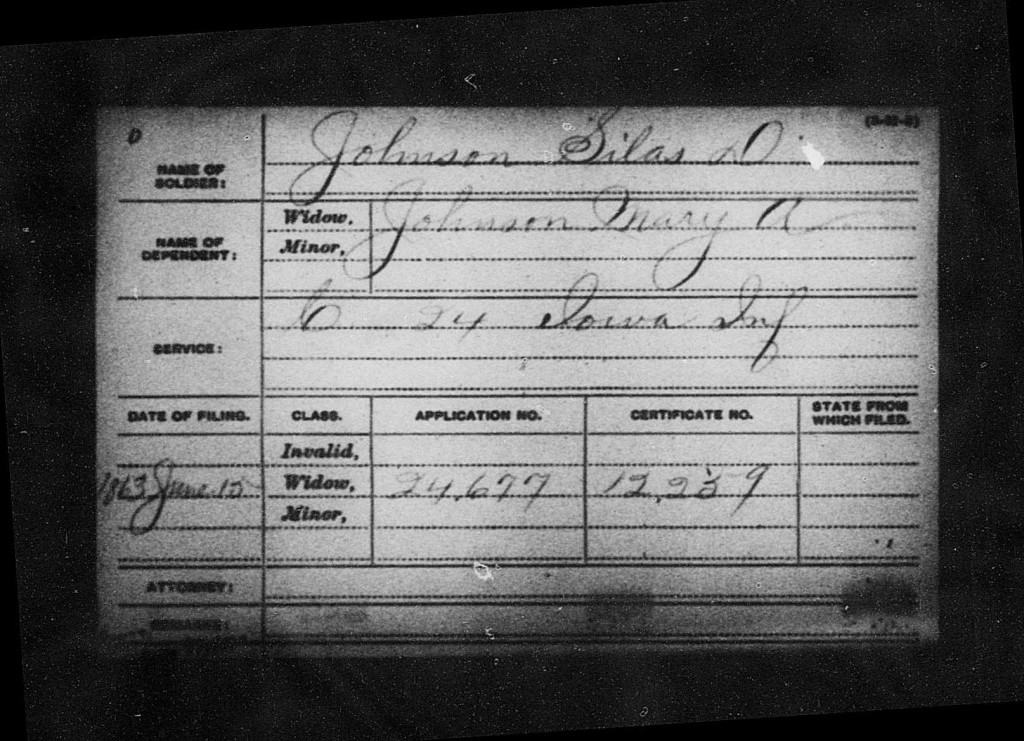

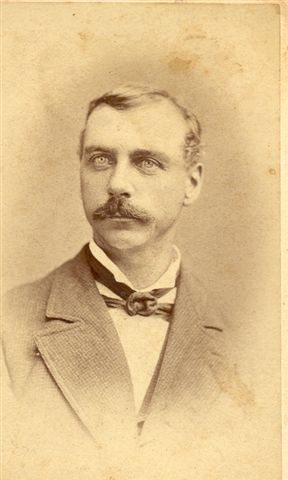

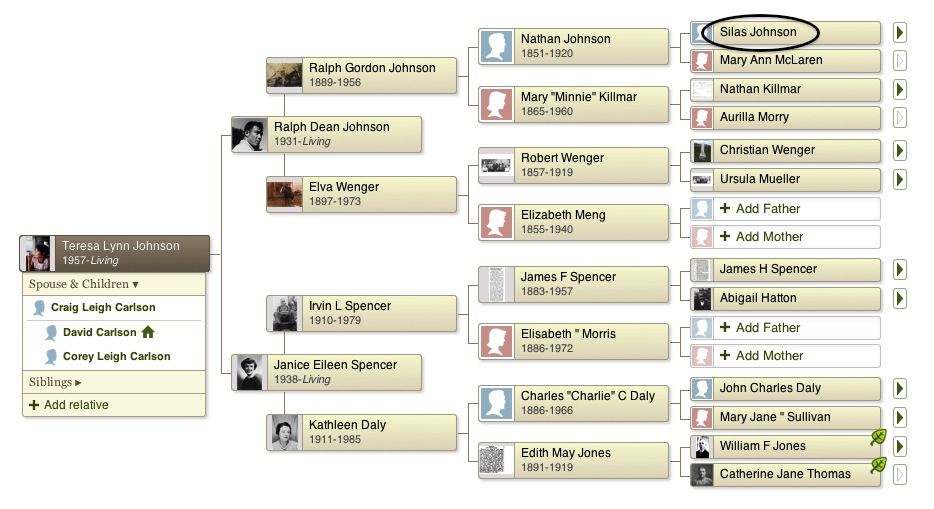

Silas Drake Johnson was born on October 20, 1822 in Holmes County, Ohio to Griffith Johnson and Harriet (Drake) Johnson. He was married to Mary Ann McClerin on August 3, 1843 in Holmes County. They had seven children: Frank A. (b. October 31, 1845), Joseph S. (b. January 30, 1848), Clarence Delano (b. November 12, 1850), Nathan H. (b. September 19, 1851), Alice Ervilla (b. May 4, 1856), Adda Estelle (b. September 26, 1858), and Agnes Erminnie (b. April 13, 1863). The family was living in Center, Cedar, Iowa in 1860. Silas was a farmer.

In June of 1863, Silas registered to fight as a Union Captain in the Civil War. His heroic end is detailed in History of Iowa From the Earliest Times to the Beginning of the Twentieth Century (Volume 2) by Benjamin F. Gue:

“THE TWENTY FOURTH IOWA INFANTRY

Soon after the President’s call for 300,000 volunteers of July 2, 1862, Governor Kirkwood authorized Eber C. Byam, of Linn County, to raise a regiment. Three companies were accepted from Linn County, two from Cedar, two from Jackson, one from Johnson, one from Tama and one from Jones, making in all nine hundred fifty men. E.C. Byam was appointed colonel; J. Q. Wilds, lieutenant-colonel; Ed Wright, major; and C.L. Byam adjutant. The regiment went into camp at Muscatine in August, 1862, and on the 18th of September was mustered into service of the United States.

On the 20th of October it was embarked on a steamer, reaching Helena, Arkansas, on the 28th, where camp was made on the bank of the Mississippi River. This proved to be an unhealthy locality and soon more than one hundred men were prostrated by sickness. The regiment remained here most of the winter, from time to time engaged in hard marches and fruitless expeditions. On January 11th the regiment embarked on the White River expedition under General Gorman, and endured almost unparalleled hardships and sufferings, which cost the lives and health of hundreds of those who composed that unfortunate army.

Upon the return to Helena the old camp and city were found to be inundated and a new encampment had to be prepared on a range of hills. When the floods subsided, mud almost unfathomable prevailed everywhere. A rainy winter came on, in which drilling was almost impossible, and long dreary hours and days were passed by the men cooped up in the cheerless quarters with nothing to relieve the depressing monotony. The hospitals were crowded with the sick and a feeling of hopeless despondency settled down upon the army.

Late in February, General Washburn’s expedition started from Helena to open the Yazoo Pass, and this aroused the army from the lethargy that had prevailed, and gave hope of active service in the field. General Fisk’s Brigade went with the expedition, and from this time forward our regiment had daily drill and frequent dress parade. Under the instruction of Lieutenant-Colonel Wilds, now in command of the Twenty-fourth, the regiment was becoming distinguished for its fine discipline and general efficiency.

When the army was reorganized in the spring for the Vicksburg campaign, the Twenty-fourth was attached to the Thirteenth Corps under General McClernand, Hovey’s Division. During the three months the regiment had been in camp at Helena, fifty members had died and many were in the hospitals. Of nine hundred fifty men who left their Iowa homes in October but little more than six hundred could be mustered in the ranks on the 11th of April when the fleet attempted to open the way to Vicksburg. The Twenty-fourth supported artillery at the Battle of Fort Gibson and was here first under fire. Not a man flinched and but six men were lost.

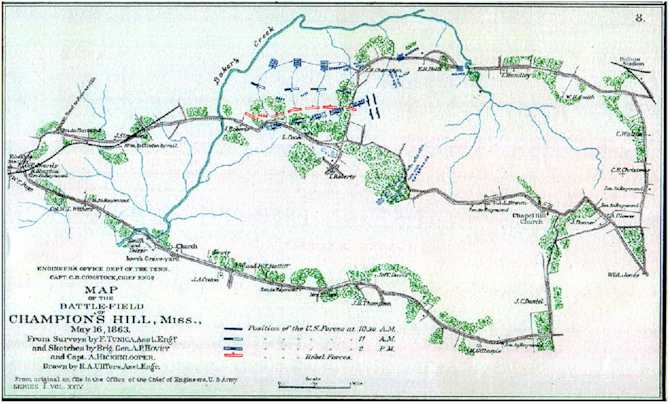

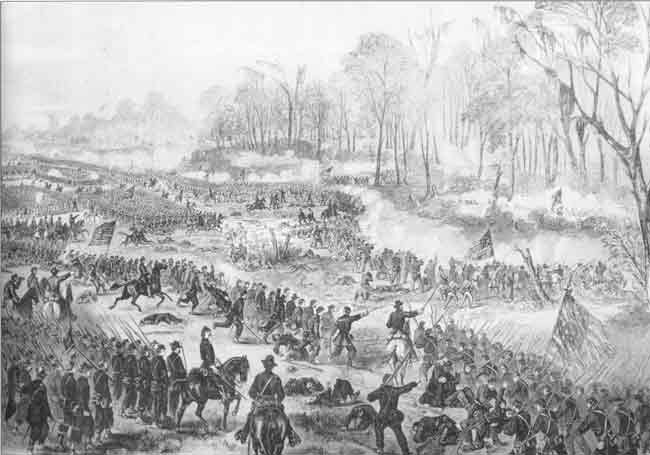

It was at the BATTLE OF CHAMPION’S HILL,fought on the 16th of May, that this regiment made its great sacrifice and won undying fame. General Grant had already won three battles since his army started to capture Vicksburg and General Pemberton determined now to move out of his stronghold and strike the Union army a crushing blow in the rear while General Johnston was engaging it in front. His plan was a good one, and if successful Grant’s army would have been caught between the two Confederate armies and cut to pieces or captured. But Pemberton had a master in the art of war to deal with. Instead of being caught in the trap so skillfully laid, Grant had sent McPherson and Sherman two days before to fall upon Johnston’s army at Jackson, while he faced about the main body of his army to meet Pemberton, ordering the detached division to concentrate near Bolton. Grant learned that Pemberton was approaching with an army of 25,000 and ten batteries of artillery, and at once directed Sherman to move with all possible speed to join the main army at Bolton.

Pemberton had taken a strong position on a ridge which was protected by precipitous hillsides covered with dense forests and undergrowth. His left rested on a height owned by Colonel Champion, which gave the battle-field its name—Champion’s Hill. McClernand was slow in reaching the ground and the battle was fought mainly by the divisions of Hovey, Logan and Crocker. Hovey moved on the main road until he came within sight of the enemy in his strong position. Deploying his division into line he attacked the whole front of the Confederate army with great impetuosity and for more than an hour the battle raged with great fury at this point. Charge after charge was made on the Confederate lines with varying success.

At one time the Twenty-fourth Iowa, unsupported, made a desperate charge on a battery that was pouring a destructive fire into our ranks, and captured it. Carried away with the enthusiasm of their brilliant achievement the men rushed on with shouts of victory until checked by a terrible fire of musketry from greatly superior numbers. In this charge Major Ed Wright was wounded, Captains Silas Johnso

Hovey held his position for more than an hour and a half amid a most terrific fire of musketry when his lines were forced back by overwhelming numbers. Fortunately at this juncture he was reënforced by Crocker’s Division and, again returning to the attack, the combined forces finally, by severe fighting, broke the enemy’s lines, reënforced by Logan, the enemy retreating in great confusion down the Vicksburg road, artillery and many prisoners falling into our hands.

The enemy was now driven from every position, beaten and in full retreat, but our losses had been very heavy in this by far the greatest battle of the campaign. The killed, wounded and missing in our army were 2,457, of which Hovey’s Division lost more than 1,200. The Confederate army lost more than 2,000 prisoners, twenty pieces of artillery and General Tilgham killed.

Of the Iowa regiments engaged in this battle the Fifth, Tenth, Seventeenth, Twenty-fourth and Twenty-eighth were in the thickest of the fight and were particularly distinguished for their bravery. The Twenty-fourth lost one hundred ninety-five men, of which forty-three were killed and forty mortally wounded. The regiment bore a prominent part in the siege and capture of Vicksburg, and few suffered more or accomplished more in bringing about that great victory.”

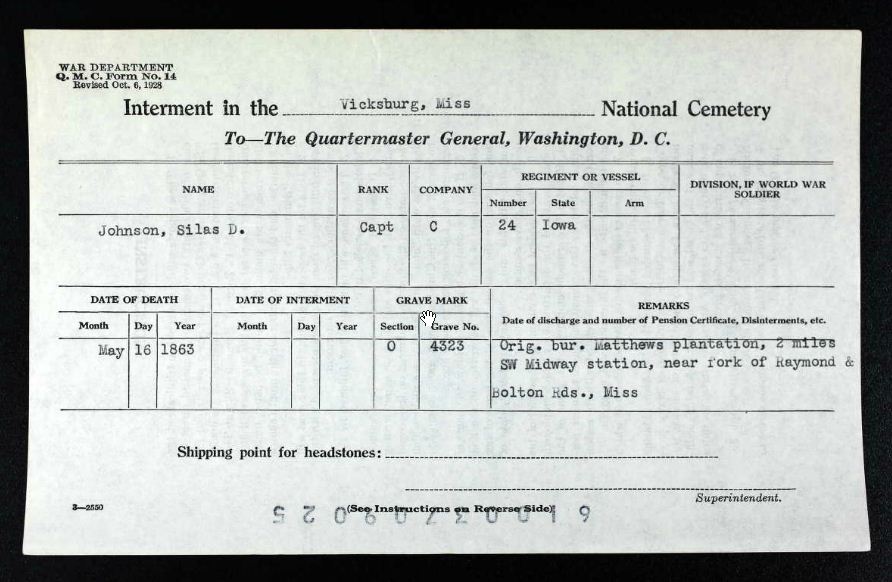

Silas Johnson died a Civil War hero on May 16, 1863 in the Battle of Champion Hill in Vicksburg, Mississippi. He was buried at the National cemetery in Vicksburg.