Elizabeth Perrin was born in 1770 in Chester County, Pennsylvania to John Perrin and Sarah (Kelly) Perrin. Her grandfather, John Perrin, established an early American trading post near the Pennsylvania/Maryland line, along the Potomac River north of an old abandoned Indian Village called Shawnee Old Town, in the 1740s. His son, John Jr. (Elizabeth’s father), married a sister of trader Robert Ray in 1750 in Ray’s Town (now called Bedford, Pennsylvania). In the year 1756, John Jr.’s (first) wife and daughter were killed by Native Americans in a raid in Bedford County, as explained in this article from the Bedford (Pennsylvania) Gazette in 1907 by J. H. P. Adams:

“Robert Ray, the founder of Ray’s Trading Post on the Raystown branch of the Juniata river where Bedford now stands in 1750, was a first cousin to the Powell’s. While attending to his trading post in September, 1756, he was taken sick. Powell, Perrin, and Huff and Vogan brought him from his trading post to Joseph Powell’s where in the course of time he got much better. He went to Perrins, some six miles distant, where in a few days he died and was buried on Perrins farm, now owned by the widow of William Dicken. Your correspondent showed his grave to Doctor Enfield while he was sheriff of Bedford county.

John Perrin’s first wife was a sister of Robert Ray. She was captured at the same time that Mrs. Vogan, Mrs. Clark, Mrs. Davis and Mrs. Tombleson. This Indian raid was made by the Shawnee Chief Wills. After traveling some three miles Mrs. Perrin was unable to keep up with the fleeing Indians. On the point of Tussey’s mountain, near two white rocks, called Perrins Rocks, she was killed and scalped with her infant baby. The alarm being given, the Indians and their captives were pursued by Perrin, Davis, Vogan, Clark, George and Joseph Powell and Michael Huff. These men came up with the Indians on the top of Wills’ mountain. They found that the captors of the women had been joined by about one hundred other savages. The pursuers hoped that during the night they would be able to release the captives. When morning came the Indians held a council, when about seventy-five of them with the captives started west, the others going north, except Chief Wills, who remained at the camping place till late in the evening when he also left camp and was carefully followed. At dark they discovered a small light on the very pinnacle of Wills’ knob . Cautiously approaching, George Powell discovered the Indian Chief alone and in a sitting position, but he soon lay down on the ground. When morning came and the sun began to show over the western horizon the old chief raised himself to a sitting position. Powell was upon the alert and at the distance of seventy steps; when his firelock rang over the still mountain range the old chief’s spirit took its flight to the Happy Hunting Ground. His “topnot” was removed, his grave dug and his body laid therein. The body was removed about the year 1825 by unknown parties. The grave is still there and will be till time is no more. Any person that is skeptical as to this fact can visit the spot and see for himself as your correspondent has done.

The surviving women were found at Montreal, Canada, and brought home some six years afterward.” Descendant Richard Perrin Day unearths inaccuracies in this story in his thorough and fascinating Perrin history.

The Indian raids were a result of John Penn’s deception of the Indians in his attempts to secure the “Western Purchase” of Pennsylvania. He tricked them into giving him title to a vast tract of land from the Susquehanna westward. When the natives, who did not understand such land contracts, realized they had given away their hunting grounds, they united with the French in an effort to regain their land by force. Attacks were made on all English settlers in western parts of the colonies by burning their homes and crops and killing/capturing those who could not protect themselves. These attacks caused virtually all families in western Maryland and Pennsylvania (mostly isolated) to abandon their homes and head eastward.

The Perrin family owned various tracts of land along the valley adjacent to Murley’s Branch. The branch, fed by numerous springs, runs NNE along the west side of Warrior Mountain to a gap in the mountains where it turns east and empties into Town Creek. The valley extends north beyond the branch to the Pennsylvania line. In the early years before the colony had advanced its settlements, the area was traversed by Indians coming from as far away as New York, through Pennsylvania and Maryland into Virginia and further south.

John Perrin, Sr. was a tanner by trade, and through his contact with most of the men in the area made known his holdings in western Maryland. He died in 1770 in Frederick County, Maryland, and by terms of his will requested that all property be sold by his sons, John, Joseph, and Edward, and the money be divided equally among them. Over the years, literally hundreds of acres of his estate near Murley’s Branch were sold off and divided between his children.

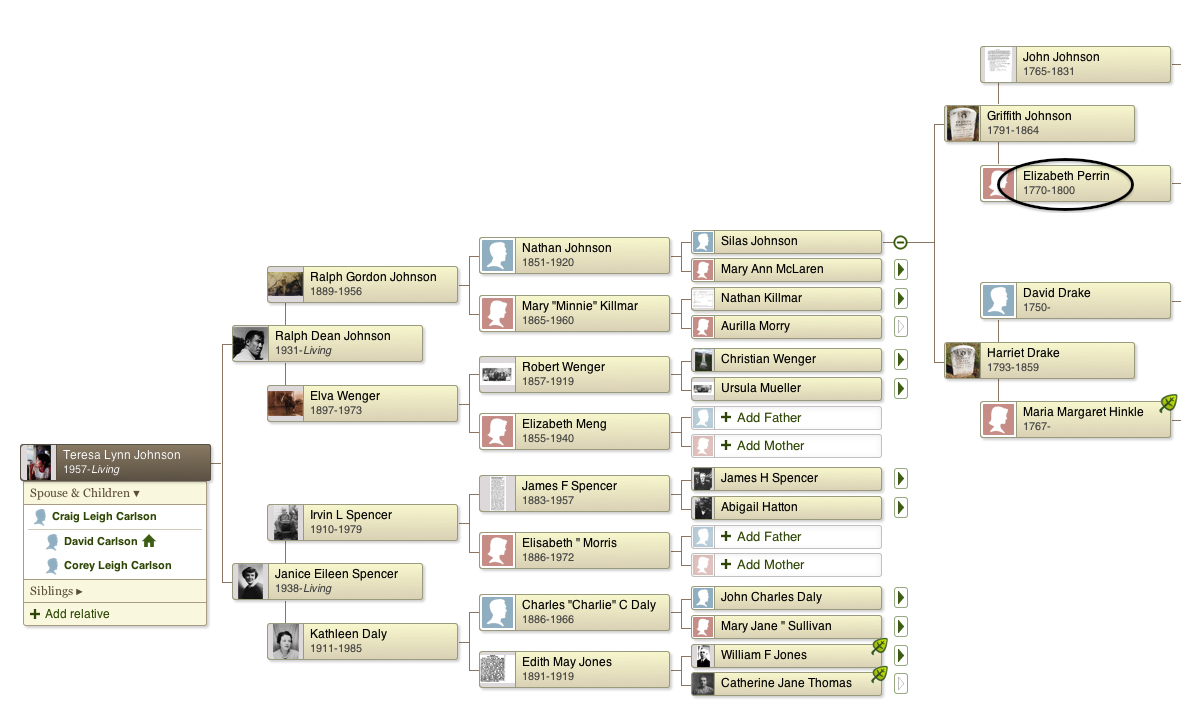

John Perrin, Jr. and his brother Joseph eventually settled in western Maryland. John remarried twice after the murder of his first wife, and he returned to Bedford County. He had a total of 22 children and passed away in 1785. Two of his daughters by Sarah Kelly, Elizabeth and her sister Drusilla, married sons of Revolutionary War Capt. Griffith Johnson. Drusilla married Benjamin Johnson, and Elizabeth was married to John M. Johnson. Both families moved to Ohio in 1799.

John Johnson and Elizabeth had five children: Griffith (b. 1791), Benjamin, Nathan (b. 1795), Elizabeth, and John (b. 1799). Elizabeth died around August of 1800 at the young age of 30 in Nottingham Township, Harrison County, Ohio.