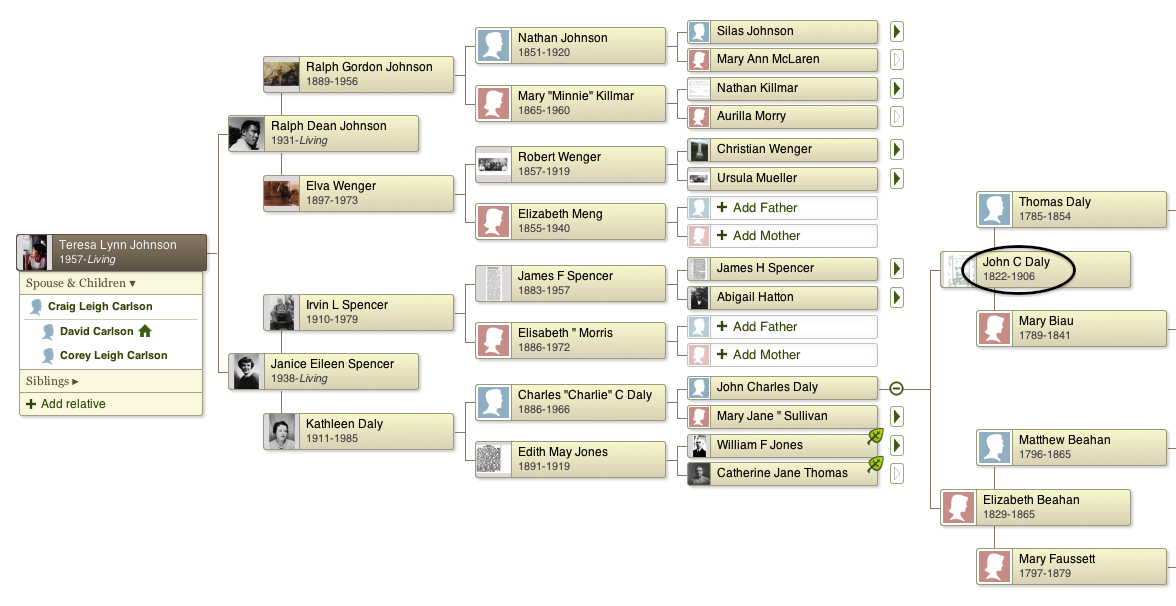

John C. Daly was born on May 20, 1822 in Meath, Ireland to Thomas Daly and Mary (Biau) Daly. He was the fourth in a family of nine children, all of whom were born in Ireland. He emigrated to America as a young man. He never spoke much about his life in Ireland, but when we read Irish history, it’s no mystery why the family decided to come to America.

Reports on the conditions in Ireland at this time tell us that “the people were not only poor; but they were wretchedly poor.” The poor had nothing to live on but what they could raise on the land, and the rich lived on the rents which were wrung from the wretchedly poor tenants. It was said that people in the North lived on meal, potatoes, and milk; in the South on potatoes and milk; and in the West on potatoes. Between one potato crop and the next, millions were driven to beg on the roads for their food.

Those were the physical conditions which prevailed in Ireland when John Daly was growing up. The political conditions were just as bad. During the seventeeth century, the land was taken from the Irish Catholics and given to Protestants, many of whom came from England. Later, laws were passed, making it impossible for a Catholic to own or acquire land. Any large tracts that were owned by Catholics were given to Anglo-Irish or Enlgish Protestants, and laws forbade marriage between Catholics and Protestants. After years of this kind of treatment, Catholics were looked upon as an inferior class by the English, and they themselves came to accept this position of inferiority.

In 1839, when John was seventeen years old, his parents came with the family to America, landing at Boston. There were Thomas and Mary, the parents; Jane, the eldest daughter, then about 32, accompanied by her husband, Patrick Coan, and two sons, William and Patrick; Patrick, aged about 30; Matthew, 29; John, 17; Thomas, 16; Christopher, 15; Lawrence, 10; Mary, 7; and Michael, 6. We do not know how long they stayed in Boston, but soon after their arrival, Lawrence died and is buried in Boston. Sometime later Jane’s husband was accidentally shot by someone playing a practical joke with a supposedly unloaded shotgun.

Mary, the mother, died in 1841 and is buried in Flint, Michigan, so it is likely that they moved there in 1840 or ‘41. They settled on a farm one mile south of Mt. Morris, and one mile east on the Stanley road, living in a log cabin. The first Mass in the vicinity was said in this log house sometime around 1850, as related by Mary Jane Hughes, a grand-daughter of Thomas Daly.

On February 20, 1849 he was married to Elizabeth Beahan (daughter of Matthew Beahan and Mary “Polly” Faussett) in Flint, Genesee, Michigan. They had seven children: Linus (b. November 8, 1850), George Beahan (b. September 30, 1852), Mary Florence (b. July 9, 1854), Julia Helen (b. August 3, 1856), John Charles (b. December 16, 1858), Edward (b. October 11, 1860), and Austin (b. November 5, 1862).

After their marriage, John and Elizabeth lived for about seven years on a farm two miles southeast of her home. Late in 1856 they moved to Clark County, Missouri, where they settled in a little town then known as Santa Fe. It was later renamed St. Mary’s, but is not in existence today, according to the Secretary of State of Missouri, unless it is now the town of St. Patrick. There John went into partnership with a man named Elwood in a grocery store.

Slavery was a burning question at this time, especially in Missouri; it being the most northern state in the Louisiana Territory in which slavery was allowed. The Missouri Compromise “forever prohibited slavery or involuntary servitude” in any other state of the Territory north of the south boundary of Missouri, but this was upset by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854; and in 1857 the Dred Scott decision of the Supreme Court killed the Missouri Compromise. Looking at these dates, we can imagine how hot the political arguments were in that state at the very time when the Daly family settled there.

John’s partner, Mr. Elwood, was a sincere abolitionist, who evidently talked too much and to the wrong people. One night he was taken out by a mob and hanged in his own orchard.

Soon after this the store failed, and John Daly moved his family across the river to Lima, Illinois, where he ran a wood-yard during the later years of the Civil War.

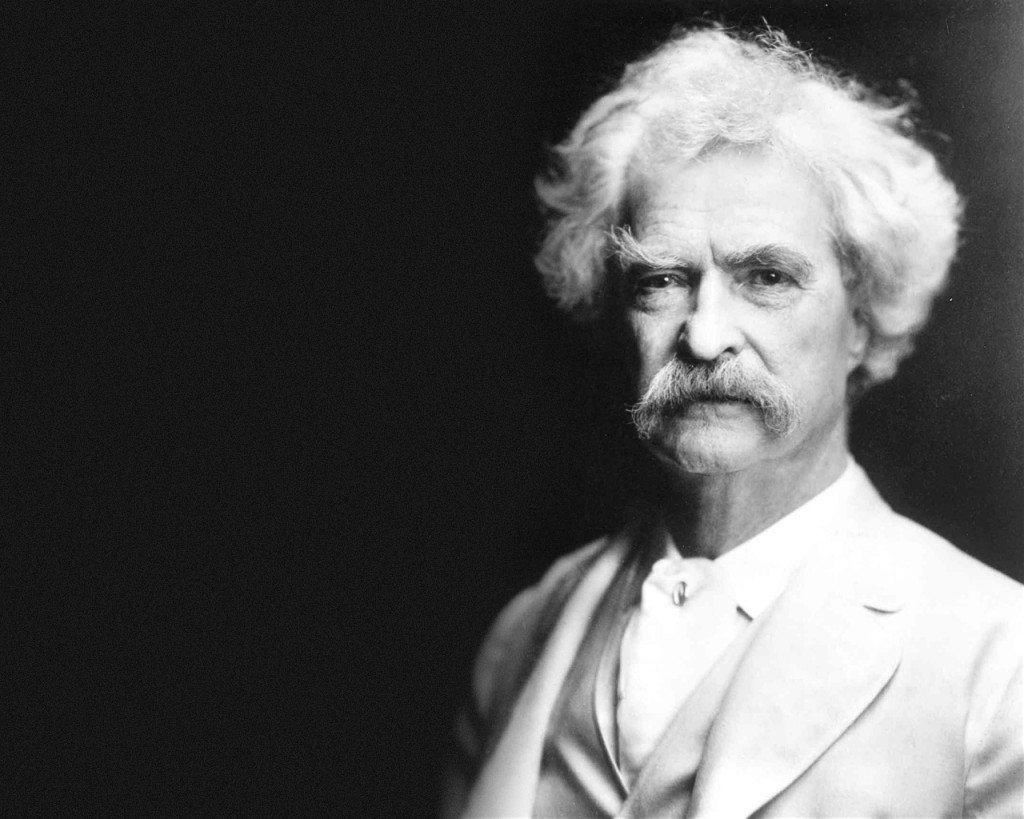

In “Life on the Mississippi,” Mark Twain says: “Mississippi steamboating was born about 1812. At the end of thirty years more it was dead! Alas, for the wood-yard man! He used to fringe the river all the way; his close-ranked merchandise stretched from one city to the other along the banks, and he sold uncountable cords of it every year for cash on the nail; but all the scattering boats that are left burn coal now, and the seldomest spectacle on the river now is a wood-pile. Where now is the once wood-yard man?”

During this time the famiy lived in Missouri, the three youngest children were born; John Charles in 1858, Edward in 1860, and Austin in 1862, on November 5th. Just three years later, on November 5, 1865, Elizabeth died at the age of 36 in Lima, Illinois. Soon after her death, the family returned to Michigan, where they went back to the Matthew Beahan farm where Elizabeth’s mother still lived. Her father had died sometime before.

We have little record of the time between 1865 and 1880, but this next few years must have been a difficult time for John Daly. Just two years after their return to Michigan, Linus bled to death as a result of an accident with a pitch-fork in the hayfield. Shortly afterwards the grandmother, Mary Beahan, died.

Florence and Julia were married in Flint, Florence to Theodore George and Julia to John Nelson.

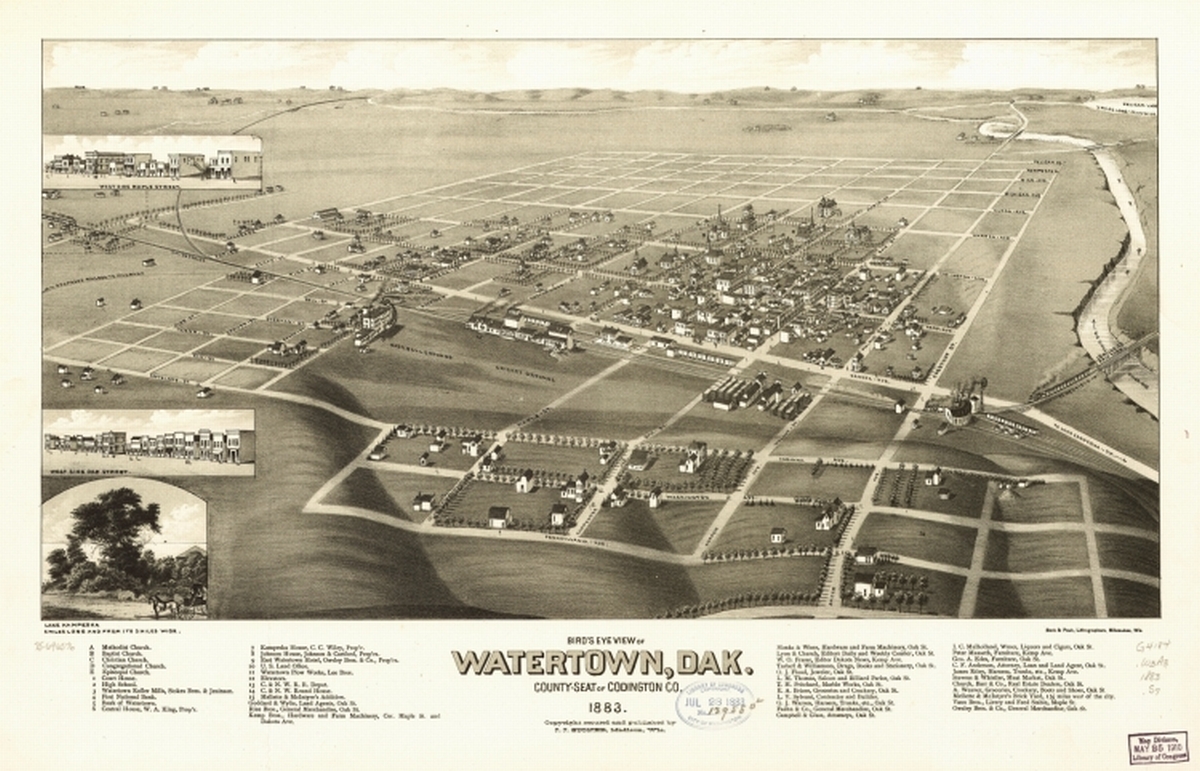

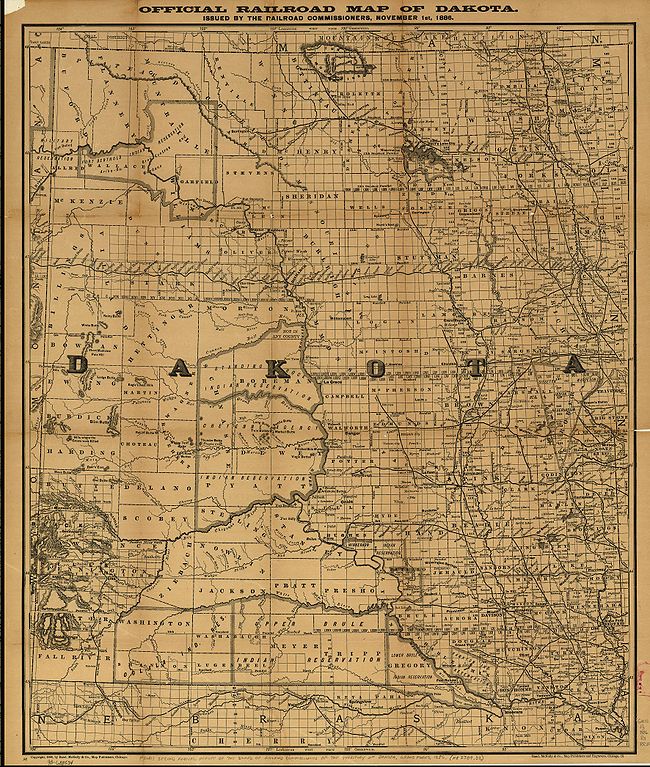

In 1880, John and his four sons left Michigan and went with J.D. Lavin to Watertown in the Dakota Territory, which was the end of the railroad at the time. Early in the spring of 1880, a rush of settlers began in earnest, and Columbia (also in the Dakota Territory) was the objective point. John D. Lavin was a stockholder in the townsite. In Watertown, the Dalys and Lavin bought a team and light wagon, and made their way to Columbia. John’s son George brought the first copy of the laws of the territory to Brown County with them.

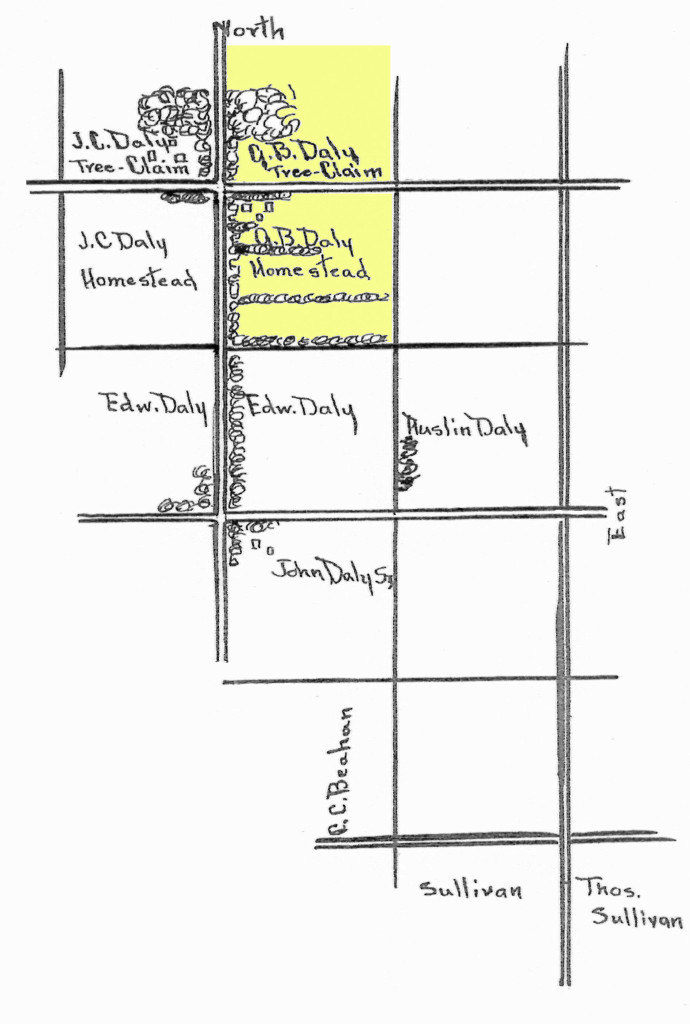

George Daly filed his pre-emption claim two miles east of Columbia, but in order to get a tract large enough so that they could all have their farms adjoining, they had to go two miles north and seven miles east of Columbia, where they located their land [as shown on the sketch map]. In order to file on the land, they drove overland to Jamestown, the nearest point on the Northern Pacific Railroad, and took the train to Fargo (the land office for the district). They filed on the land April 9, 1880. Many other Flint people, including Charles C. Beahan, brother of Elizabeth, took land nearby.

An in-depth account of (John’s son) George Beahan Daly’s life can be found here:

Julia and her family came out later and lived nearby on different places, until they bought their own place three miles southwest of her father’s farm. Florence was the only one who remained in Michigan. After living on his claim for a few years, Eddie sold his land to Alex McFarlin and returned to Michigan, where he spent the rest of his life.

John Daly was troubled with asthma all his life, which was probably the cause of his being very stoop-shouldered. He made many trips back to Michigan during the winters, possibly for his health, and to visit relatives. After a few years in Dakota, he thought his asthma was cured and he persuaded his sister, Mary Hughes, who also suffered with asthma, to visit him there. She came out with [John’s brother] Chris Daly’s family and stayed for about a year; but the houses were cold, being newly built of green lumber, and she returned to Michigan.

John’s sons, George and Johnnie, married Hannah and Minnie Sullivan, daughters of Thomas Sullivan, whose family, also from Flint, had homesteaded nearby.

Eddie and his father “batched” together until Eddie returned to Michigan. Frank Daly, son of Chris, says of John: “He was a real good cook. He was a good shot, too. He could drive along and shoot a rabbit right over the horse’s head.”

Austin worked in Columbia, part of the time as a turnkey at the Columbia jail. His cousin, Chris’s daughter Julia, says of him: “He was a handsome lad, too. He went out on a call one night, whether social or business, I can’t remember, and was never seen again. His death was very hard on Uncle John.

In his later years, John was not able to work his farm, but he always raised a large garden, and drove around the country selling vegetables, with a singly buggy and his little black horse, “Billy.” Part of this time he lived with his son Johnnie or his daughter Julia, in their homes.

In the late ’90s his son George built a small one-room house for him, just east of George’s house and attached to it. Here he kept house and did most of his own cooking. George always took him his oatmeal ready cooked for breakfast every morning. Up until the last years of his life he kept a garden in some part of one farm or another. His grandchildren used to make spending money pulling weeds in his garden. He always enjoyed reading the newspapers, visiting with friends and relatives and playing “pedro” with his grandsons in the evenings.

After living in the little house for a few years, he had it moved across the road on the corner of George’s tree-claim under the cottonwood trees. Possibly the fact that there were thirteen children in George’s family had some influence on his decision to move to a more quiet spot. A year or more before his death, he had become very feeble, and Julia persuaded him to have his house moved to her farm, where she could look after him, and there, on October 20, 1906, he died at the age of 84 years.

The John C. Daly family donated the land for the Columbia school, which was named Daly Corner School. The descendants of the original Dalys still live on these farms, at Daly Corner near Columbia.