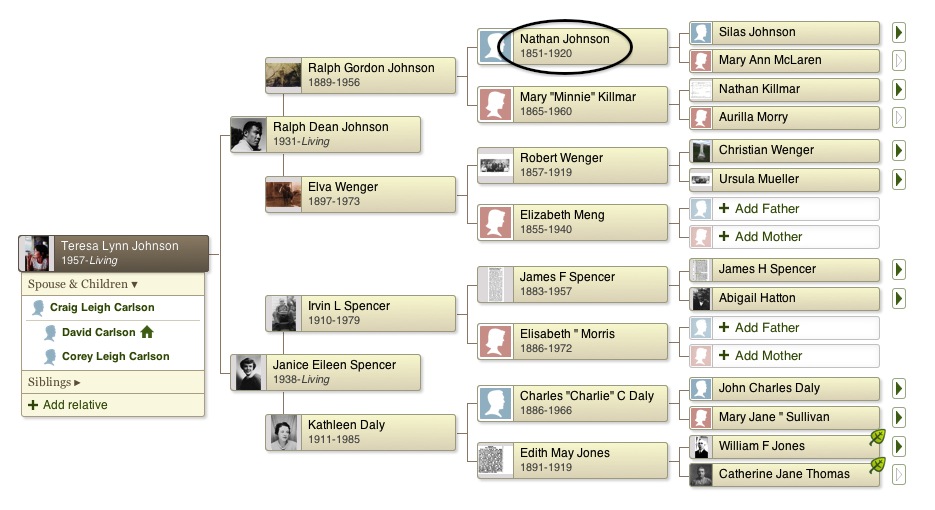

Nathan “Nate” Hamilton Johnson was born on September 19, 1851 in Holmes County, Ohio to Silas Johnson and Mary Ann (McClerin) Johnson. In 1878, at the age of 27, Nathan made the arduous trip to Brown County, South Dakota, where he became one of the county’s original settlers. The allure of free land made the trip worthwhile…a homestead was about 350 acres.

His brother, Clarence, had arrived in Brown County the year prior. He built the first house in Brown County that same year, and it was completed in early 1878. Along with Ole, Ben, and John Everson, Nate settled along the east bank of the James River in the spring of 1878.

In “History of Brown County,” George B. Daly takes an in-depth look at the long, hard road to the Dakotas faced by the early settlers:

THE FIRST SETTLEMENT

In mid-August of 1877, the broad expanse of what is now Brown County could have been seen lying under the hot sun, in the full glory of midsummer, but without the home of a human being anywhere on its face. The bison was gone: the grass grew in the trails that converged to their old watering places: their bones were everywhere, bleaching in the abandoned pastures that awaited the herds of another era just at hand.

Journeying northeast along the old government trail that led from Ft. Pierre to Ft. Sisseton came a little party of homeseekers, the first to enter Brown County. They had left the Missouri River August the seventh, 1877 and traveling slowly, one wagon being drawn by oxen and one by mules, they were about two weeks on the road. The party consisted of Clarence D. Johnson, William Young and his sister, Hattie, who later became Mrs. Gruenwald, and a man named Reynolds. They had been on the Missouri River some years in the wood business, and were well-seasoned frontiersmen. Clare Johnson had served a term in the regular army at western outposts from ‘66 to ’69.

This old military road, the only kind of thoroughfares yet in the valley, approached the Jim below the county line, then ran north until the fording place, where is now the York bridge, was reached. Here the party left the trail, keeping on the west side until they reached the point where the 6th standard parallel crosses the river. Here they drove their claim stakes, established their homes and the new era was begun.

Before their rights grew cold they had completed three comfortable log cabins on the high bank. Clare Johnson went back to the Missouri, where he spent the winter freighting, and the rest remained. The winter was an open one and passed without incident to the first residents of the county. In the spring, April being half gone, they were surprised one morning to see two men approach the east bank of the river. On going down and talking with them they found that they hailed from Blue Earth, Minnesota, and were Ole and John Everson. They had left Ben Everson and William Hawes down the river about a day’s journey and were trying to find Sand Lake upon which they understood there was a large body of timber. They ‘Went on north but returned toward night reporting only little brush on an island they could not reach. They concluded to go back and bring the rest of the party up and locate claims on the east side somewhat farther down. They came up accordingly, driving their covered wagon, in which, among other necessary articles, they carried a plow and two fiddles. They drove two yoke of oxen. After looking about some they took the claims which the Eversons still occupy (1905). Nathan H. Johnson next came over from Ft. Bennett, where he had been employed the previous year, and took the claim on the east side which he still occupies.

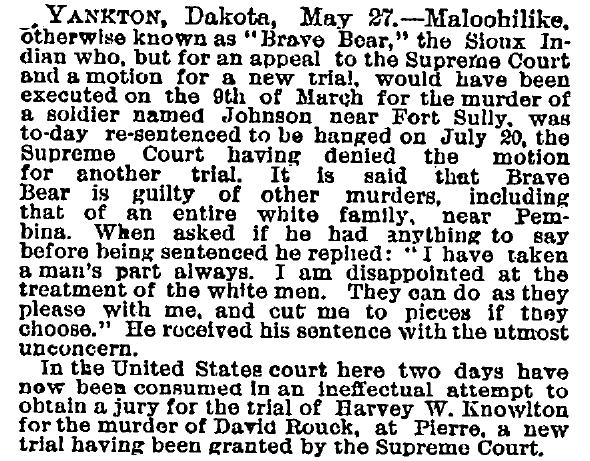

Nathan’s brother Joseph was killed by a Sioux Indian known as Brave Bear. Nathan wrote a letter in 1914 to R.J. Courtney of Okobojo Township [South Dakota] detailing the event:

AN EARLY MURDER AND ITS PENALTY

The following letter and newspaper clipping will tell the story of the murder in 1879 near the big cottonwood tree on the creek in Okobojo township, of Joseph Johnson; also the capture and conviction of the Indian murderer. [This cottonwood tree ended up in the front yard of the Glessner homestead a few years later. SG]

Mr. Courtney:

Dear Sir:

I received your letter quite a while ago, but have been pretty busy so haven’t answered it, but will try to now.

Joseph S. Johnson was my brother and had been working at Cheyenne River Agency eight miles up the river from Fort Sully on the west side of the river. He stayed all night with Jim Pearman at Fort Sully the night of the 14th of May, 1879 and on the morning of the 15th he started for the Jim River, all alone, horseback. He had written to my brother, Clarence and me, wanting one of us to come over and meet him at Fort Sully and come back with him. But we got a letter from my mother and sister that they were going to start from Mt. Vernon, Iowa, to get ready for them, so we thought we could not spare the time.

Mother and sister came, and I met them at Watertown on the 15th of May. I also got a letter from Joseph there at Watertown. We waited two weeks and not hearing from him, my brother, Clarence, and a man by the name of Blackwell went over. When they got within thirty miles of Sully they left the old government trail and took a short cut in to the fort, and the men here said that he had left on the 15th. It was dark when they got to the fort so in the morning they started back on the old trail, and after going about twenty-five miles, on Okobojo creek they found him in the water, covered with some brush, stripped of all his clothes, and with two fingers cut off to get the rings. Joseph had told Jim Pearman that he had a thousand dollars in money. Everything was gone and we never got any of it.

This Brave Bear, in the fall of ’78 helped kill a family in Minnesota and was put in jail at Fort Totten, northeast of here. He and his partner broke out of jail and the other one got killed, but Brave Bear got away and came down here and was telling some Indians that were camped here about helping to kill that family. He went from here to Fort Thompson and from there to Spotted Tail agency, where he stayed all winter. He came back to Fort Thompson in the spring of ’79 and was coming up the river with a man by the name of Agar, a Frenchman. They would keep back on the bluffs in the day time and come into camp at night. Agar said that Brave Bear had all the things when he came into camp on the night after killing Joe.

Brave Bear went with Sitting Bull, into Canada, and came in with Sitting Bull in the fall of ’81 to Fort Yates. He was arrested at Bismarck and tried at Yankton and hanged in the fall of ’82. If any or all of this is of any use to you, you are welcome to it.

Yours Truly,

Nathan H. Johnson

An article in the Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette from November 16, 1882 entitled “Brave Bear Hanged: A Sioux Indian Chief Pays the Penalty” gives us a morbidly thorough picture of the execution:

YANKTON, November 15–Brave Bear, a Sioux Indian Chief, convicted of the murder of Joseph Johnson, near Fort Scully, on the 15th of May, 1879, was hanged to-day in the jail yard, the execution being private. The Indian was taken from the jail to the United States Marshal’s office, in one of the upper rooms, at noon, and there bound with straps, having his feet free so he could walk to the scaffold. After his arms were pinioned he called for a man who could talk Indian, and with but little delay an interpreter was procured from the outside, and Brave Bear had a few moments’ private conversation with him in the Sioux language. He made no confession, but did not deny the deed for which he was convicted. He asked the interpreter to send word to his people to make no attempt to avenge his death, kill no horses and omit all customary mourning exercises. He also asked that the message he had sent to his people to be conveyed to the President of the United States, that the Great Father might know he had given good advice. At the conclusion of his talk Brave Bear was led to the place of execution, just outside the building. He mounted the scaffold with a firm tread and stood upon the trap which was so soon to drop from beneath him and hurl him into eternity. His legs were securely pinioned by straps and buckles, the rope adjusted about his neck and the awful moment had arrived. The black cap was drawn over his face and then most of the attendants stepped back to the sides of the platform. Brave Bear was beginning to weaken, and it was necessary for a couple of officers to stand near to sustain him. In his nervous agitation he caught hold of the drooping rope as it swung in front of him and clung to it with the fingers of his pinioned hand. An officer released his hold and moved the rope back out of his reach. Thus he stood, bound hand and foot, with his head covered by the black cap, awaiting the signal which was to send him to instant death. A priest advanced to his side, whispered a few words of prayer, and then stepped back to the edge of the platform. The officer in charge pulled the string which rang the bell in the Marshal’s office. A man concealed within the room, in response to the signal, jerked the rope attached to the trigger under the scaffold, and at 12:30 o’clock the drop fell. The Indian shot through the opening, and as the rope pulled there was a cracking sound. He struggled for a few moments, but the end came quickly. Soon there was nothing but a convulsive twitching of the muscles. In fifteen minutes from the time the drop fell Brave Bear was pronounced dead by the attending physicians. Fifteen minutes later the body was cut down and delivered to the undertaker, who caused it to be buried in the Catholic cemetery. There was little excitement attending the execution. Everything was orderly and the affair was consummated without accident. This is the first instance where an Indian has been hung in Dakota for a crime against a white man.

From Standing Rock Agent John McLaughlin´s book “My Friend the Indian” ~

CHAPTER IV

BRAVE BEAR AND THE ONLY ONE

Notable Indian Crimes The Slaying of the DeLormes Ghastly

Forms of Indian Mourning How One Elk held his Father-in-Law.

“HEN Brave Bear was hanged for his crime, his father, an old Indian of the Cut Head band of Sioux, came and sought me out at the agency.

“Is my son dead?” asked the father.

I was nonplussed, for it was not given me to carry on without feeling a conversation with a father about a son who was hanged the day before. But I had to make the best of it. The old man was very earnest and not at all angry though he might have charged me with trying to rid the world of Brave Bear long before he was finally overtaken by the fate that was

appointed him from the beginning.

“He is dead,” I answered.

“Are you sure he is dead ?” persisted the old man.

” I have a telegram saying that he was hanged yesterday,” said I.

“It is well,” rejoined the old man. ‘We are glad, his mother and myself, for he was a bad son.”

And this frightful declaration was as near eulogium as was ever pronounced on Brave Bear, a murderer and habitual criminal – – which few of his tribe have been. They have been guilty of deeds of blood, but none of them were sneaking murderers for a little gain, as Brave Bear was. Even The Only One whose distinctive appellation might have pointed him out as a notable exception to the common run of his people, and whose hands were imbrued in blood spilled for gain – – was a very decent sort compared to his companion in crime, Brave Bear. And he escaped the ignominy of the death that was the portion of Brave Bear, dying in a desperate attempt to escape after the most sensational sort of capture, and being mourned in the most heart-breaking and barbarous way by his wife, one of the handsomest women of the Sioux nation – – a people not wanting in women with physical attractions.

Brave Bear was a sort of Indian dude. The Only One was quite the contrary – – by no means the distinguished individual that the hopes or fancy of his parents painted when they gave him a name that indicated how high a place he had in their esteem. Brave Bear always had plenty of clothes, cheap jewelry, all the things that go to make the dandy at an Indian agency – – or did go to make such a personage in the days when civilized garb was not so common as it is now. How he maintained his well-dressed habit I don’t know, but suppose from his finish that it was not by honest means. These men were not much given to living close to the reservations, but roamed about the settlements a great deal. They might have lived by thievery.

In any event they attained distinction in the field of high crime, when they found it to their purpose to commit a frightful butchery while engaged in robbing a settler named DeLorme, near Pembina, North Dakota, in 1873. They had entered a stable for the purpose of stealing horses, and when two of the owners arrived on the scene, they shot and killed both, and a third man was mortally wounded. In the house were two women, and the Indians attacked them, shooting and wounding both of them. One of the women put up her hands to defend herself from a blow aimed at her head by Brave Bear, who carried a sword, and who struck her with it. The blow cut off one of her fingers, laid open her scalp, and stretched her apparently dead ; but she recovered, as did the other woman. Brave Bear and The Only One rifled the place, stole several horses, and escaped to the Missouri River country, passing through Devils Lake reservation, where I then was. As soon as I learned of the tragedy, I was convinced that Brave Bear and The Only One were of the party who had perpetrated the crime. They kept away from Devils Lake agency; but, having learned the facts of the murder from trustworthy Indians, I reported them to the proper authorities.

I heard nothing of them for several years ; but one day in the winter of 1878 word was brought to me that they had arrived at Devils Lake and were living among the Cut Head Sioux at the west end of the reservation. Everything pointed to them as the authors of the butchery at Pembina. It was common knowledge among the Indians that they had committed the crime, but the people were afraid to interfere with them. They were bad men, whose presence among the Indians and impudent indifference to the authorities were demoralizing. Having convinced myself by inquiry that there was no doubt of their guilt, I made arrangements to capture them in the early spring, before their ponies were in condition for them to start out on their usual summer raids.

The capture, to be made without bloodshed, must be effected by surprise, and it must not fail, for with the Indian, even more than with the white man, nothing succeeds like success. It would be useless to attempt to take the men in their camp. They would assuredly fight, and that was not necessary. But they were very shy of coming to the agency. The only thing to do was to call a council of their band. They could not absent themselves from this without making themselves too conspicuous for safety, and once in the agency council-room we might handle them.

At the time two troops of the Seventh Cavalry, Ouster’s old command, was in garrison at Fort Totten. I conferred with Captain James M. Bell, now Brigadier General Bell, retired, who commanded the post, and arranged with him for the necessary troops when needed.

Planting time was approaching, and I sent out a call for a council, to which all adult male members of the Cut Head band were invited, and required to attend; the ostensible object of the council being to ascertain the acreage of land each family intended to cultivate that year, so as to determine the quantity of seed needed. The council was to be held in the assembly hall, which was on the second floor of the main building of the agency group. In the rear was my office. The door to this was to be guarded by employees of the agency, with one of the more muscular at each of the two front windows, Thomas J. Reedy guarding one window and Frank Cavanaugh the other. It was arranged to have an armed squad of dismounted soldiers paraded behind the garrison buildings, where they could not be seen from the agency, so that when Brave Bear and The Only One had entered the council-room the detail would, upon a prearranged signal, double-quick to the agency, file up the stairs, and secure the two Indians.

The plan worked, after a great deal of waiting and more than an even chance of failure. Every other Cut Head Sioux then on the reservation was seated in the room before Brave Bear and The Onlv One put in an appearance. They seemed to feel that they were taking some sort of chance, and only the fact that their absence would make them conspicuous brought them in finally. Brave Bear came in first and was not disturbed. Then came The Only One, who cautiously ascended the stairway; and as soon as he had entered the hall James Stitsell, agency harness-maker, who was stationed outside for the purpose, signaled the garrison, and Lieutenant Herbert J. Slocum, U. S. A., now a major of cavalry, coming from the post with a detail of eight men, in double- quick time, closed in on the landing, filed up the stairway rapidly, and before the soldiers had reached the head of the stairs leading into the room, The Only One knew that he was trapped. He bounded through the council-room and made for a door leading into the office, which was in the north end, with the evident intention of escaping through a window ; but his way was barred there by John E. Kennedy, agency clerk, and George H. Faribault, agency farmer, whereupon he rushed back toward where I was standing, near the front door, and being pointed out to Lieutenant Slocum, was soon in the hands of the soldiers. The other Indians were tremendously excited, but I soon quieted them by announcing that no others were to be molested, and most of them knew that Brave Bear and The Only One were guilty of murder. There was no interference by the assembled Indians, and the men were taken downstairs, The Only One going first between a couple of soldiers, and Brave Bear following. They passed out of the hall and down the stairway, which was on the outside of the south front of the building, and the foot of which was only a few feet from the southeast corner. Neither of the prisoners was bound, as it was not thought that any attempt at escape would be made. As they reached the corner of the building, The Only One made up his mind to take a desperate chance. It was only about twenty-five yards to the rear of the building. Once around the corner he could afford to take a chance on being shot down, and there was the open country – – which he had occupied in defiance of arrest for so long – – before him. To refuse the chance meant incarceration, and almost certain death. The Only One did not stop long to think about the chances. He took them. With one bound he was out from between the files of soldiers. A few more bounds took him around the corner of the building, and he was off for the open country. The soldiers of his guard were astonished for a moment, then took after the fugitive, who had slipped out of his blanket and was running free. In the meantime Brave Bear was closed in on. The officer in charge, Lieutenant Slocum, drew his pistol and stepped up beside the man. The rest of the guard was ordered to the pursuit of the runaway. Slocum was not taking any chances on Brave Bear, but he wanted to be in with the chase.

“Here, Jack,” he cried to J. E. Kennedy, agency clerk, “you take my pistol and hold this fellow, will you ? while I go with my men.”

“Not me,” said Kennedy; “I haven’t lost any Indians.”

And Slocum had to hold his own prisoner. He landed him in the guardhouse.

The Only One was then far on the road to freedom. He was giving an exhibition of sprinting that has not been seen on that prairie since. Anticipating that the soldiers would not hesitate to shoot at him, he ran, bounding high and jumping sideways every jump. Once off the agency grounds, he had a very good chance of getting away. There were sloughs to the west that would hide a pursued man, and beyond there was open ground that would subsist an Indian, especially if he had no moral scruples about other people’s property; and there was comparative safety at the western agencies. The hostiles were still out in the Northwest, and Sitting Bull was not the man to ask a fugitive who came to him if he had blood on his hands, or to hold it against him if he knew that he had killed a white man or woman. He would be comparatively safe if he could even reach the camp of the Cut Heads at the west end of the Devils Lake reservation, for there were horses to be had there. And he was making a run for his life.

The soldiers were rather anxious to get the man and needed no urging to open fire on him and very bad practice they made of it, though the mark presented by The Only One was not so easy to hit as a target might have been ; and they expended a great quantity of ammunition uselessly until the sergeant, one of those grizzled non-coms who were common enough on the frontier at that time, and are very scarce now, more ‘s the pity ! took a hand in the game. He dropped on one knee, took careful aim, and fired. The Only One dropped with a ball in his thigh. The soldiers ran up toward him, thinking he was hors de combat. In a moment The Only One made up his mind that his time had come, and that he might better die fighting than on the scaffold. He stood up, and the men saw that he had his knife in his hand. With frightful screams, part of agony from his wound and part the prompting of his enraged spirits, he ran at the men, his shattered thigh causing him to run lame at every other step. He was intent on getting at the soldiers and forcing them to kill him. The old sergeant saw what the man intended, and he concluded that it was time to put him out of business, – – that winging The Only One would do no good. Down he went on his knee again, and there was no wavering in his aim. His bullet found the heart of The Only One, and he dropped dead.

The Cut Heads were greatly excited still, and the relatives of The Only One particularly so. One young brave, a brother of Brave Bear, thinking that the entire family might be apprehended on general principles, made off to the northwest while The Only One was being pursued. Some mounted soldiers from the post, thinking he was wanted too, started after him. The Indian made good headway, but was pretty well exhausted, and might have been captured presently but that he ran into a slough. Burying himself in the mud and weeds, he eluded his pursuers until it was found that he was not the man wanted, and they were called off. But it was many a day before he could be induced to come into the agency.

This occurred on Saturday evening, and the following Monday, being ration-day, all of the Indians came in for their rations. With them came the wife and the mother of The Only One. I have, as I said, seen Indians give frightful expression to their mourning sentiments, but the grief shown by those two women was awful in its manifestations. The wife of The Only One was a magnificently proportioned and handsome woman. Her beauty was something to be talked of. When I was called out by the wailing of the women they presented a shocking sight. It was customary for the widow of a recently deceased Indian to disfigure herself, to demonstrate that her grief was boundless and that she had no regard for her appearance now that the husband was dead. They would nearly always cut off their hair without regard to uniformity as to length, and also usually scarify themselves.

The wife of The Only One did not stop at the ordinary manifestations of grief. She was a ghastly sight when I found her with her mother-in-law, the two crying out incoherent words of endearment and grief, relating the many good qualities of the dead man as a husband and son, for the taint of blood is not to the detriment of an Indian man’s standing in his family, or was not in those days. The younger woman had torn nearly all the clothing from her body. She had cut off the hair from her entire head, and much of it she had torn out by the roots. Her breasts were hacked and gashed with a knife. She had cut great gashes in the lower part of each leg, from the knees to the ankles ; she was streaming with blood and was an awful sight. The mother had gone almost as far in the expression of her woe, and had deliberately chopped off the little finger of her left hand, which among the Sioux at that time was a common expression of mourning for a relative killed. I don’t think that grief could be made to wear a more horrid front than it did that day among the relatives of the dead murderer. This awful practice of maiming one’s self as evidence of affection for the dead is one of the things that the Sioux have given up in a great measure under the restraining influences of civilization and Christianity; though the grief of the Indian is still clamorous, at least so far as the women are concerned. I have, on more than one occasion, found a family engaged in great lamentation, the women throwing ashes on their heads and wailing at the tops of their voices, and, upon inquiring, have been told that the mourning was for somebody who had been dead a year or two. Something had occurred, as a meeting of relatives who had been parted and who had not hitherto had opportunity to make common cause in mourning.

But to return to Brave Bear : he was not permitted to escape from the military guardhouse. This was rather to my astonishment, for I had not much faith in the capacity of the guardians of that noteworthy military institution to hold an Indian prisoner. I had taken chances on Brave Bear and The Only One remaining on the reservation during the winter, rather than commit them sooner to the custody of the soldiers with the moral certainty of their escape before spring. My experiences in the past had not inspired me with any great respect for the holding capacity of the post guardhouse. But it held Brave Bear fast enough until the civil authorities took charge of him. He was taken first to Bismarck and later to Fargo for trial, and the case against him was complete enough. When he was arraigned for trial, the two women who had survived the murderous attack on the DeLorme family fully identified him as one of the assailants. I was called as a witness, and it was expected that a speedy conviction would be had. But even in those days the Indian had come to an appreciation of the quibbles that make loopholes in the white man’s law. The case had not proceeded beyond the first forenoon when the counsel appointed for the defense moved for the dismissal of the indictment on the ground that the court had no jurisdiction; that the crime alleged to have been committed was stated to have been committed in Pembina County, where there was a duly organized tribunal for the adjudication of offenses, criminal and civil. The point was sustained by the court, the indictment dismissed, and Brave Bear sent up to Pembina for trial. He was put in the jail at Pembina, and one morning he was missing. With him went the horse of the jailer. Brave Bear declared afterwards that his medicine was good and had liberated him; that he had simply invoked the power of his medicine and floated up through the roof of the jail. As to the disappearance of the jailer’s horse, why, that might have been a part of the medicine.

With the speed with which the Indian can move when he is put to it, Brave Bear made his way down through the territory to the Pine Ridge reservation. I believe he found things too hot for him there, or he longed for the fleshpots of the Cut Heads, his people, on the Standing Rock reservation. In any event he left Pine Ridge agency with a stolen horse, and started north. Somewhere above Fort Sully he met and murdered a man named Johnson. He stripped the victim of this second crime and put on the dead man’s clothing. In the pocket of the vest he found $1700 in money. With the dead man’s rifle in his hand, he started across the country. Johnson was a prominent Odd Fellow, and the members of that order offered a big reward for the capture of the murderer. The crime was charged to Brave Bear. The latter eluded pursuit and made his way to the far Northwest and over into Canada, where he found asylum with Sitting Bull.

He remained with the old medicine man and appears to have been of some importance in the band now greatly decimated in numbers. In the summer of 1881 Sitting Bull, to the dismay of Brave Bear, came in and surrendered and was sent to Standing Rock agency, and Brave Bear had no choice but to go with him. That fall I took charge at Standing Rock, and Brave Bear was on the reservation until the day before my arrival. He knew me and was not in the humor to take chances on what would happen when I located him. He had cached, or said he had, a considerable portion of the money he had robbed Johnson of, and he took a white man into his confidence so far as the hidden money was concerned, offering to divide the wealth if the white man would put him across the Missouri River. The deal was made, but Brave Bear had lingered too long. Other men on the reservation had identified him, and they also knew of the reward that had been offered for his capture. He was taken across the river by his white friend and soon after held up by a party of four men who were on the lookout for him, and Brave Bear was made a captive for the last time. He was sent to Yankton, then the capital of Dakota Territory, and tried for the murder of Johnson. There was no doubt of his guilt. He was condemned and hanged.

From “History of Brown County” by George B. Daly:

COLUBMIA’S FIRST PUBLIC MEETING

It was on July 4, 1879, at Johnson’s grove that the first gathering of settlers occurred. All the settlers in the county except the stock men up the Elm came. There was no reading of the declaration or speech-making, but it was said there was plenty to eat and drink. There were baseball games throughout the afternoon, and the sound of violins with feet keeping time to them floated out over the Jim (River) all night long. John Everson and Lester Blackman were the pioneer fiddlers.

T.M. Elliott describes the early Columbia scene in “Reminiscences of Early Columbia Township”:

In those days it was necessary to make a 110 mile trip (each way) to Watertown, South Dakota for flour and other food supplies and these trips were made by ox teams or horses if you had them. Mail was delivered from Jamestown, North Dakota.

There must have been lots of buffalo slightly before this 1880 settlement five miles north of Columbia as the bank of the “Jim” River there was covered with buffalo bones and horns that could be polished to a high luster and amongst the bones occasionally arrowheads, evidence that they had been killed by Indians. The first fifty cents the writer ever earned was made by heaping up these bones in piles where they were carted off in wagons. Not bad pay for a kid of seven in the “80’s”.

Also showing a phase of the eternal triangle is the recollection of a squaw carrying a papoose stopping over night in our long sod house. She was from a Devil’s Lake, North Dakota reservation, armed with a butcher knife, and in pursuit of her boy friend who had eloped with another squaw and going to another reservation near Yankton, South Dakota, a mere “trek” of 500 miles or more arid carrying the baby on her back.

Tom Marshall, later U. S. Senator from North Dakota, surveyed Columbia Township in the early “80’s” and his camp is remembered, about five miles north of the town of Columbia.

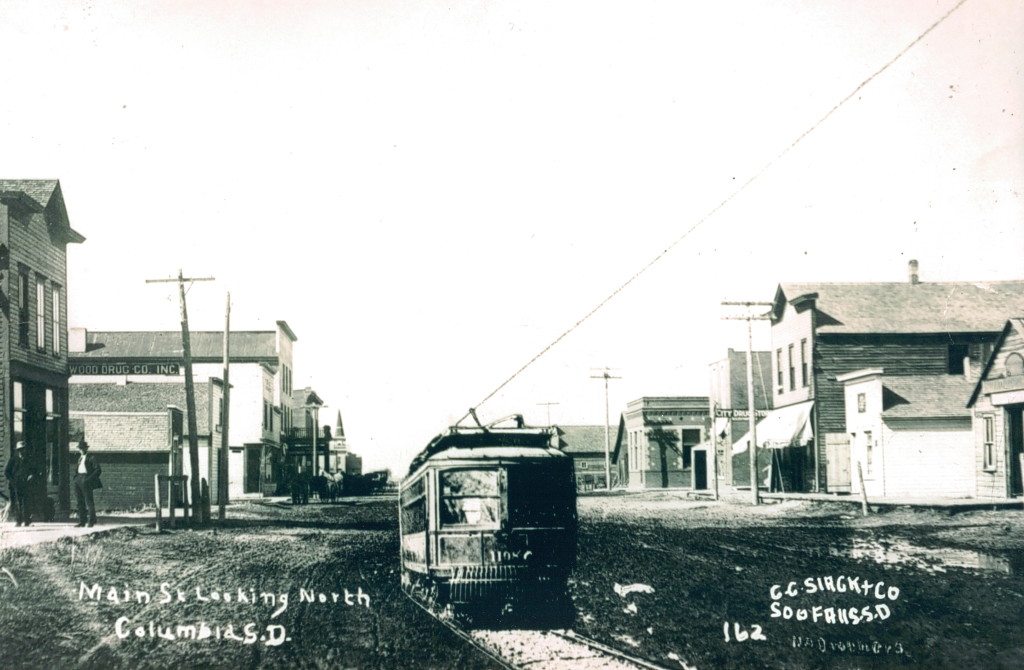

The site of the town of Columbia in Columbia Township was selected because of its picturesque environment, situated at the confluence of the James and Elm rivers and the then beautiful Lake Columbia. The river was dammed and a flour mill established by Friel or William Townsend.

Early business enterprises were the J. D. Lavin grocery and general store, Pardee grocery (no credit but he would loan the customer money to pay for their groceries), W. A. Burrington men’s furnishings, Musser and Bittman general store, Andy Stone meat market, the four story Grand Hotel, several saloons, and old timers insist that at one time there were seven drug stores and eleven hotels, possibly an exaggeration. Also Frank McCaw had a jewelry store as did Charlie Holcomb. Adene Williams had a “novelty” store, Ed McCoy and William Gilfoy each in machinery business, J. H. Jackson hardware store, William Schliebe and a Mr. Foy, blacksmiths, and John Caskin, groceries and general merchandise…

Columbia’s record as county seat of Brown County is something like “on again, off again, on again, gone again”. It seems that Columbia got the most votes at the first election for county seat and then Aberdeen got it away by some means after which the court rebuked Aberdeen for its “overzealousness” and restored it to Columbia. This writer remembers with great pleasure the triumphant return of the county records in horse drawn wagons, this being the second “on again” for Columbia. After Aberdeen got it away the second time, Columbia supporters settled back in apathetic resignation and refused to prosecute.

During the time Columbia did have the county seat, excitement was stirred up by a jail delivery one Sunday morning when Sheriff Charlie Meredith brought breakfast to the prisoners and was slugged and five prisoners escaped and fled north along the river bottoms, through the tall reeds and rushes but were recaptured about six miles from town.

When Columbia had the county seat, the fair grounds and race track were located north and east of the city limits.

For diversion in early days there was a rollerskating rink, well patronized, excursions as far north as Ludden, North Dakota on the Nettie Baldwin and Fanny Peck steamboats, toboggan slides, skating and iceboating on the lake, baseball in the summer.

The Columbia “Sentinel”, an early day paper, was published by C. E. Baldwin, assisted by Frank Elliott, Jr., in the mechanical department. Another early day newspaper published when Ordway was aspiring to be the capitol of Dakota Territory was the Ordway “Times” edited by Ezra Elliott.

The Grand Hotel, rated to be one of the best hotels west of Minneapolis in those days, housed a saloon, a jewelry store, and other business enterprises. After various vicissitudes it was finally torn down and rebuilt in Redfield, South Dakota where it is now occupied as the Eastern Star Home.

The James Block, another large office building, was occupied by early professional men and also by the Columbia Business College conducted by a Professor Hildebrandt. This building was torn down and sold for $700.00, less than the glass in the windows cost and transported to Oakes, North Dakota, the first floor occupied by stores, and the second as an opera house.

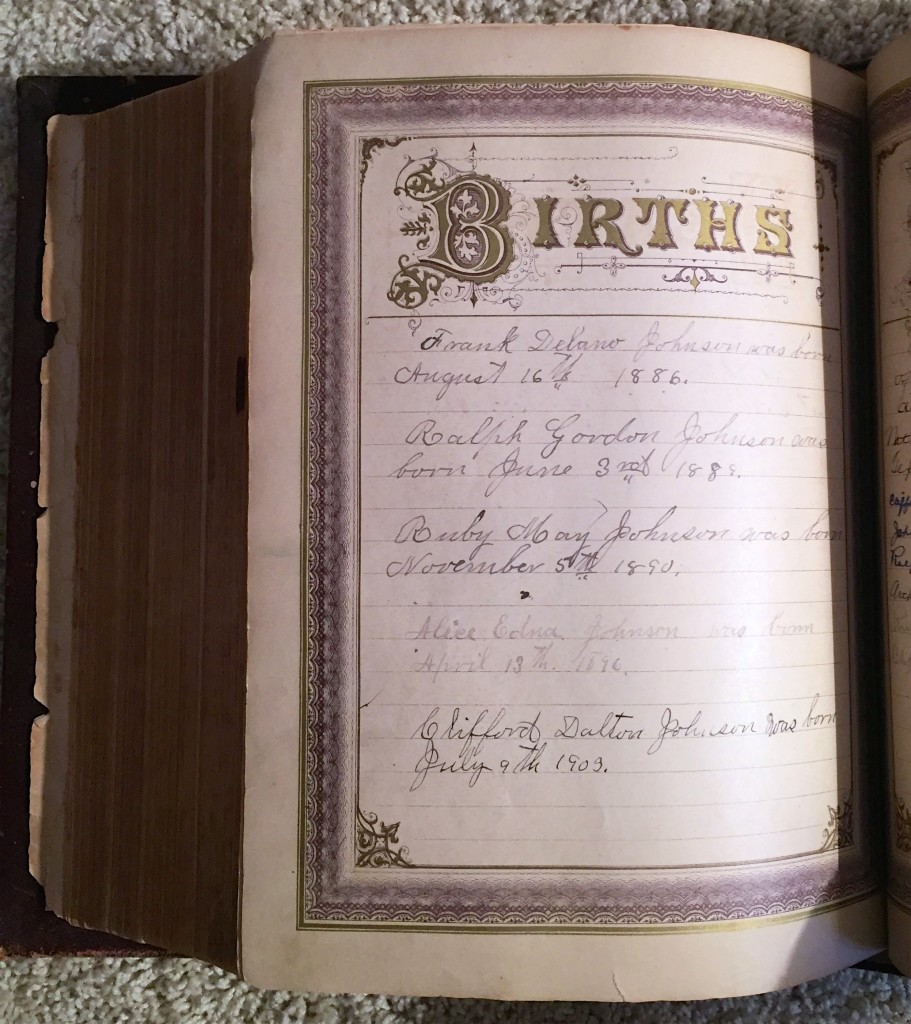

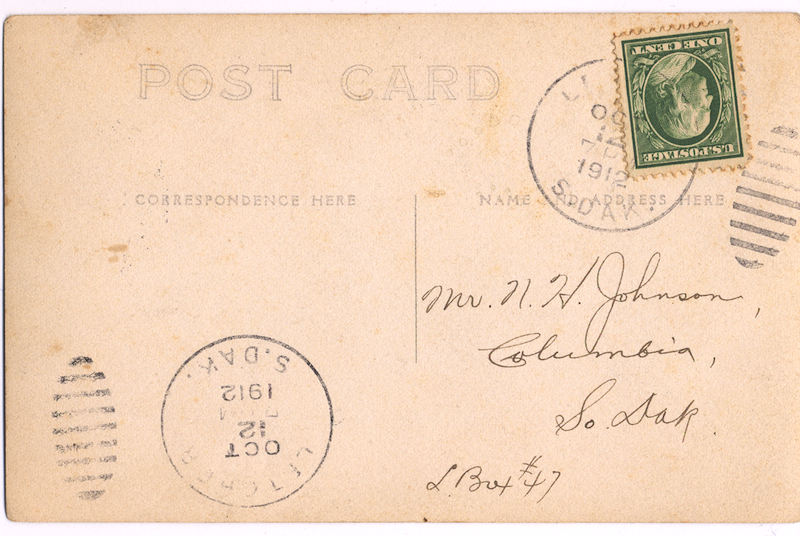

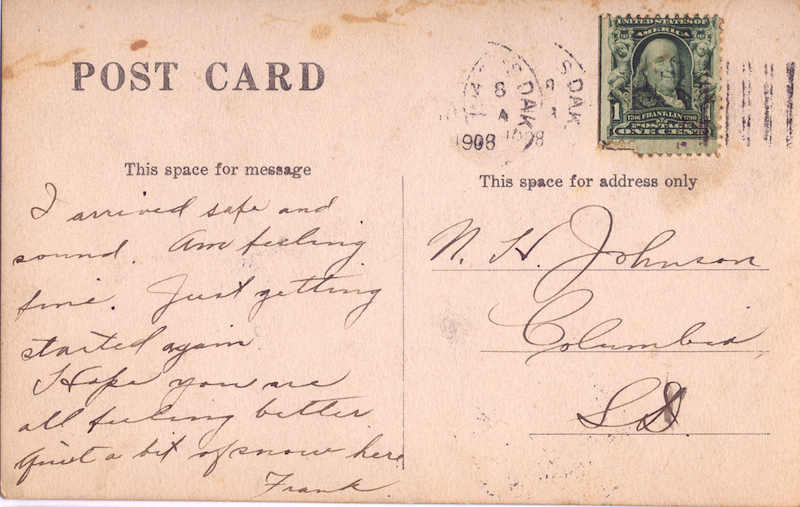

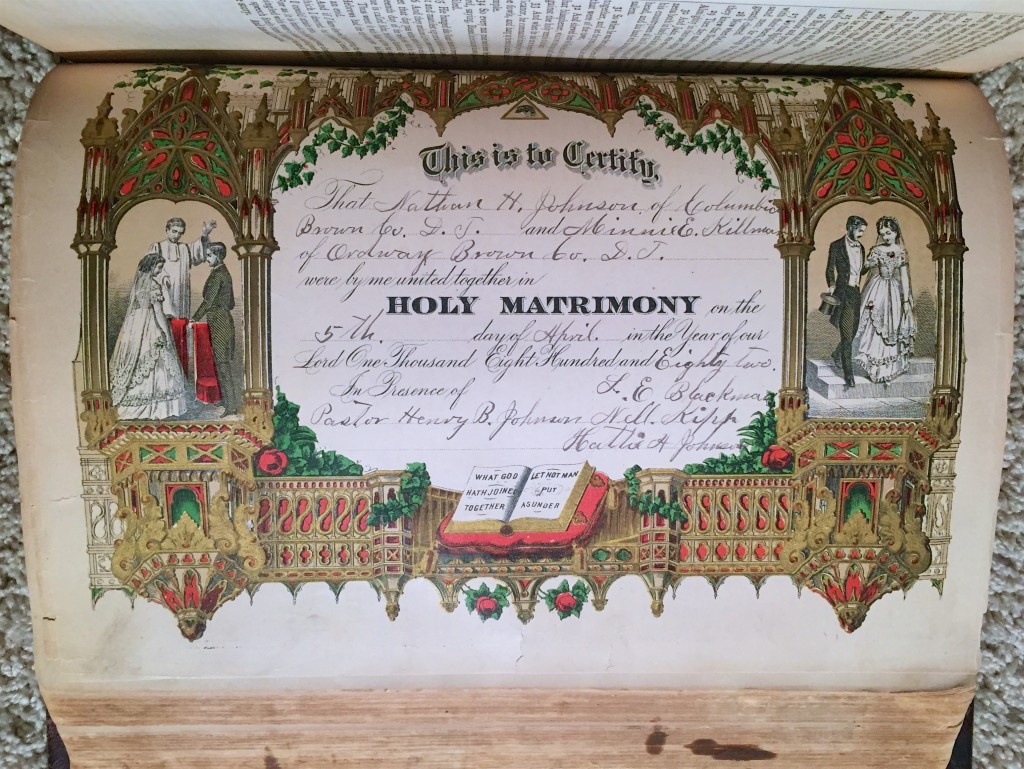

Nathan married Mary “Minnie” Killmar in Brown County in 1882, and they five children: Frank D. (b. August 1886), Ralph Gordon (b. June 3, 1889), Millie (b. November 1890), Alice Edna (b. April 1896), and Clifford D. (b. ci. 1904). Nathan was a constable in early Brown County. He was also a farmer, the patriarch in a legacy of Johnsons farming in Columbia that continues today. He died on September 4, 1920 in Columbia. Frank D. Johnson (his oldest son) was interviewed about early Columbia in 1977. Frank was 91 years old at the time.

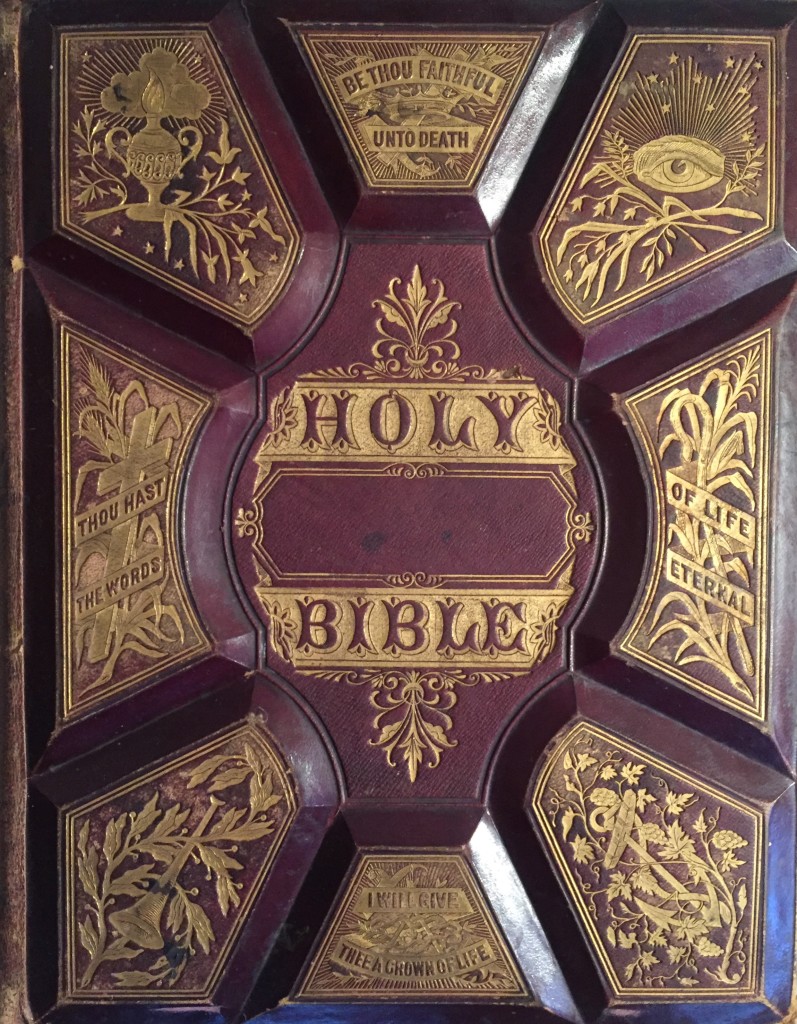

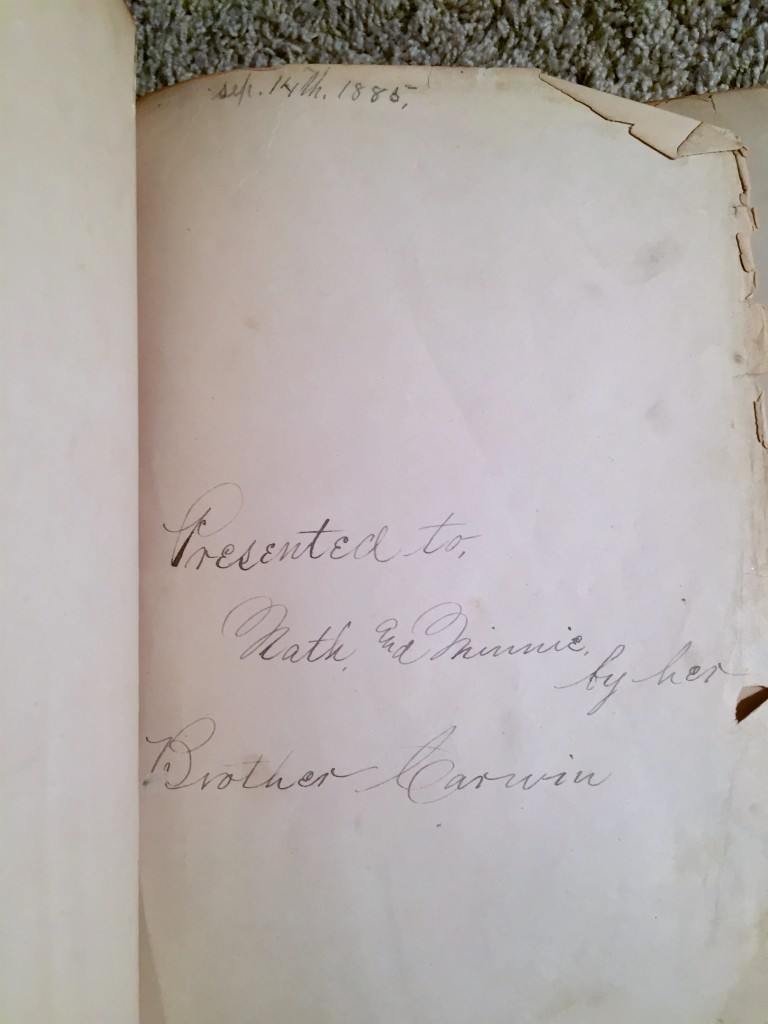

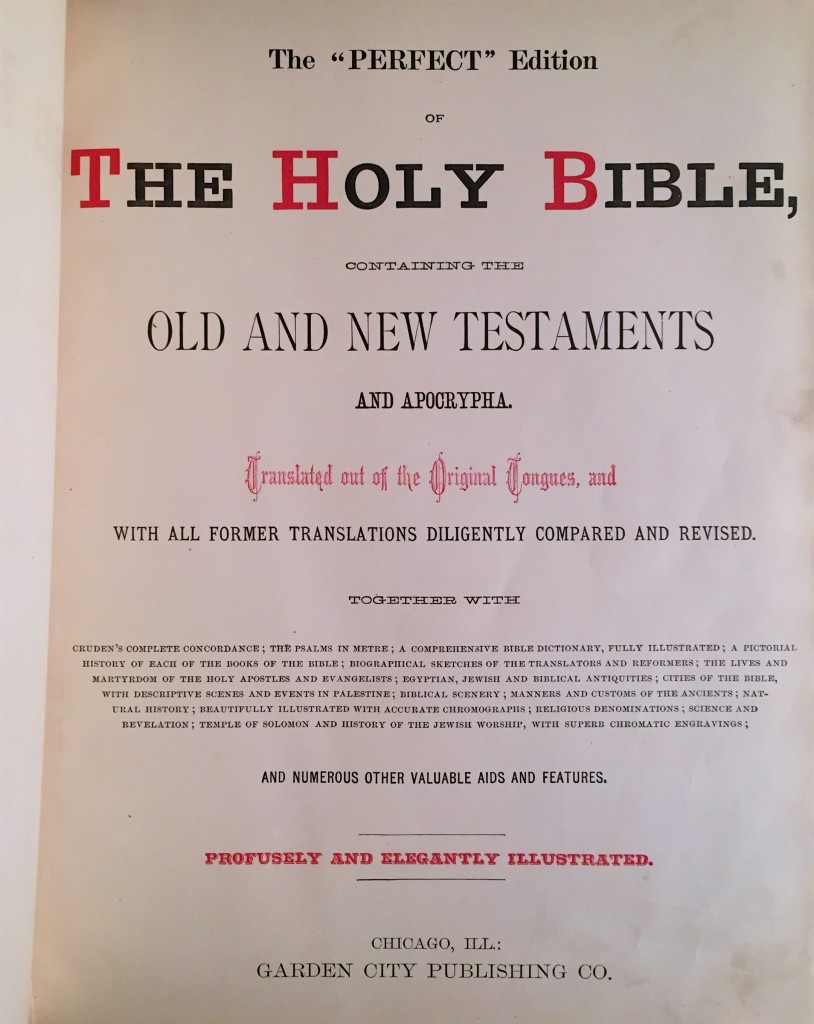

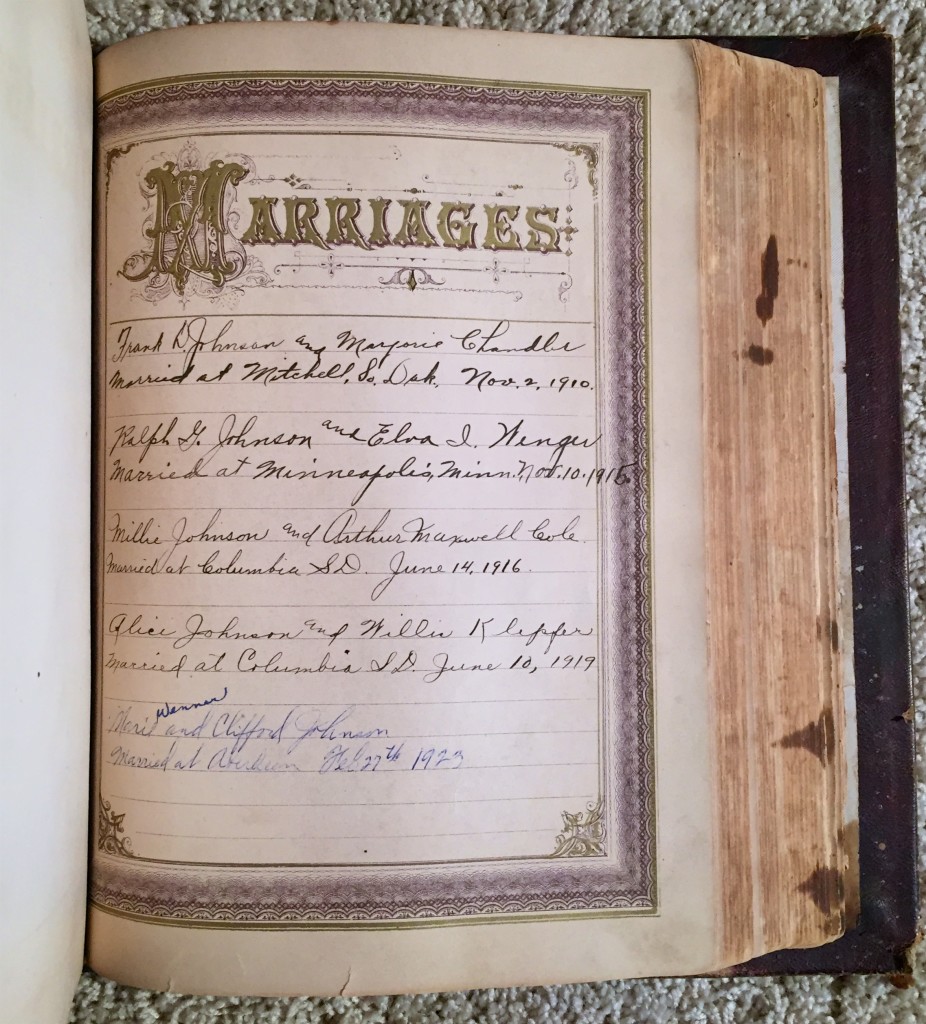

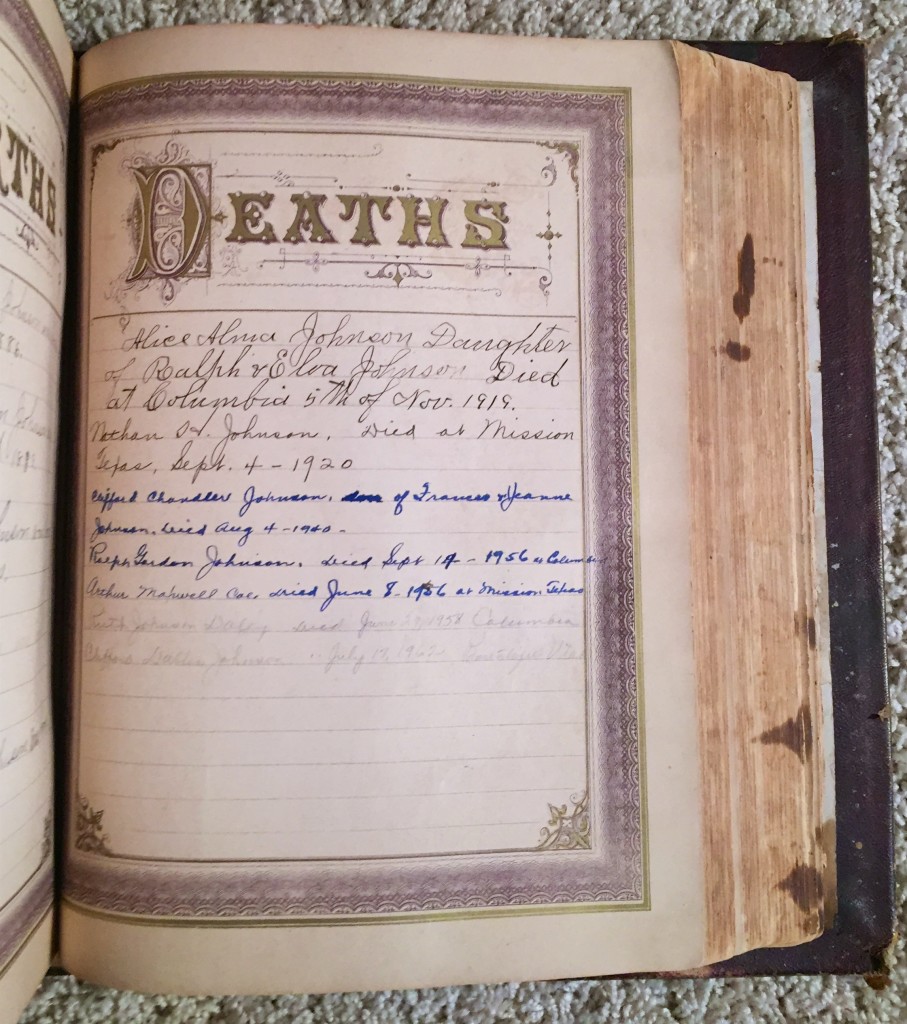

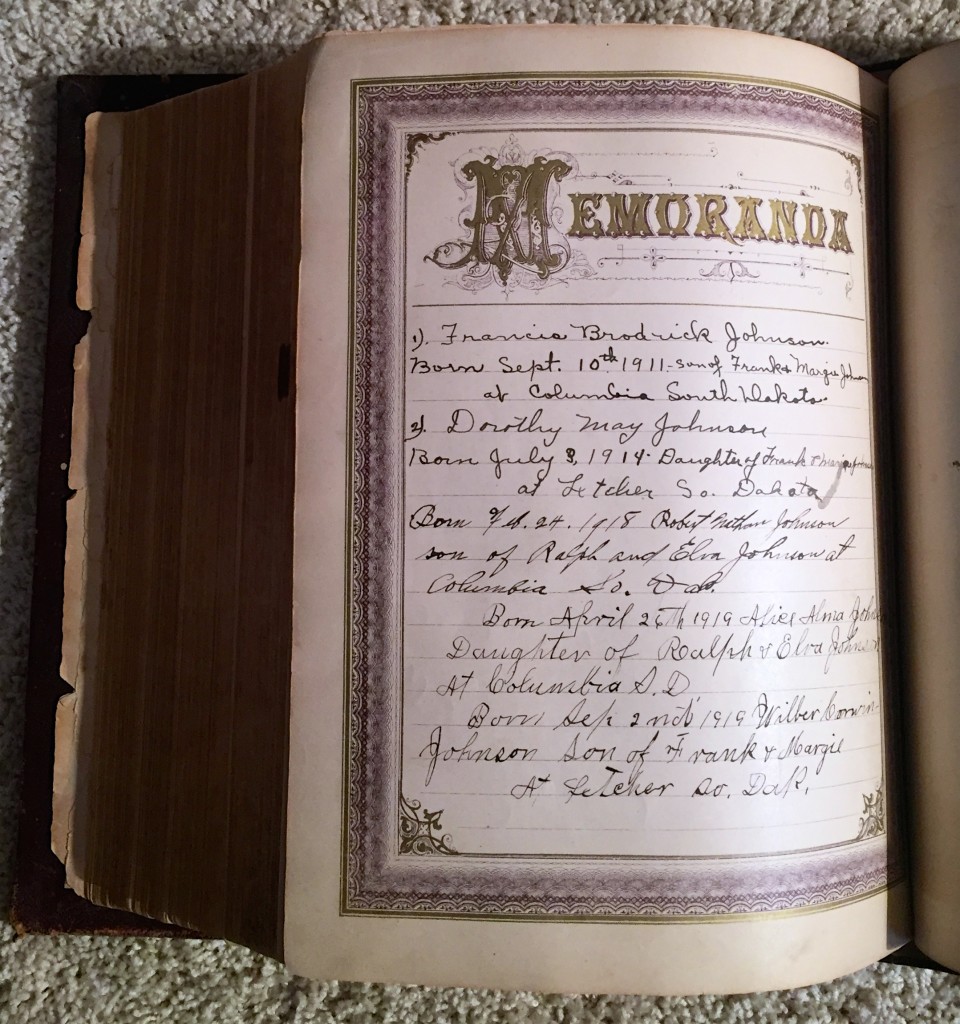

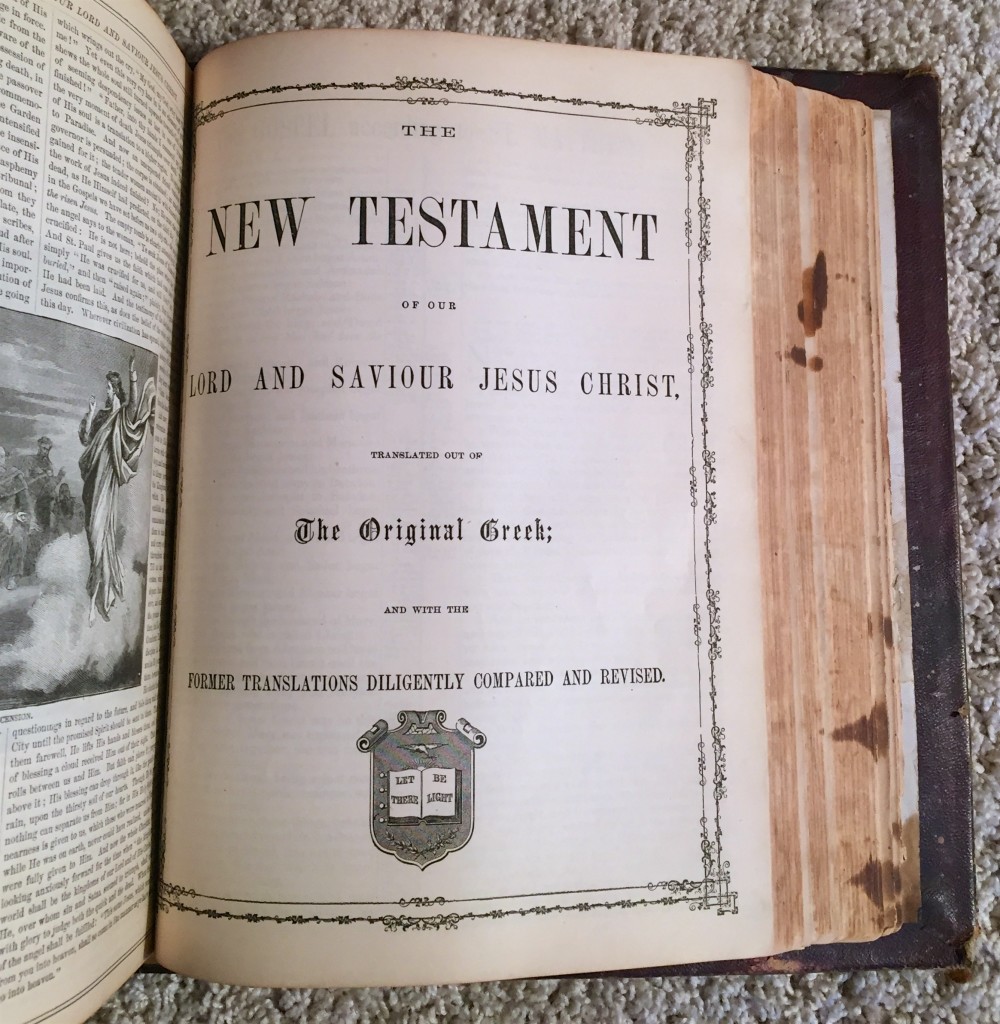

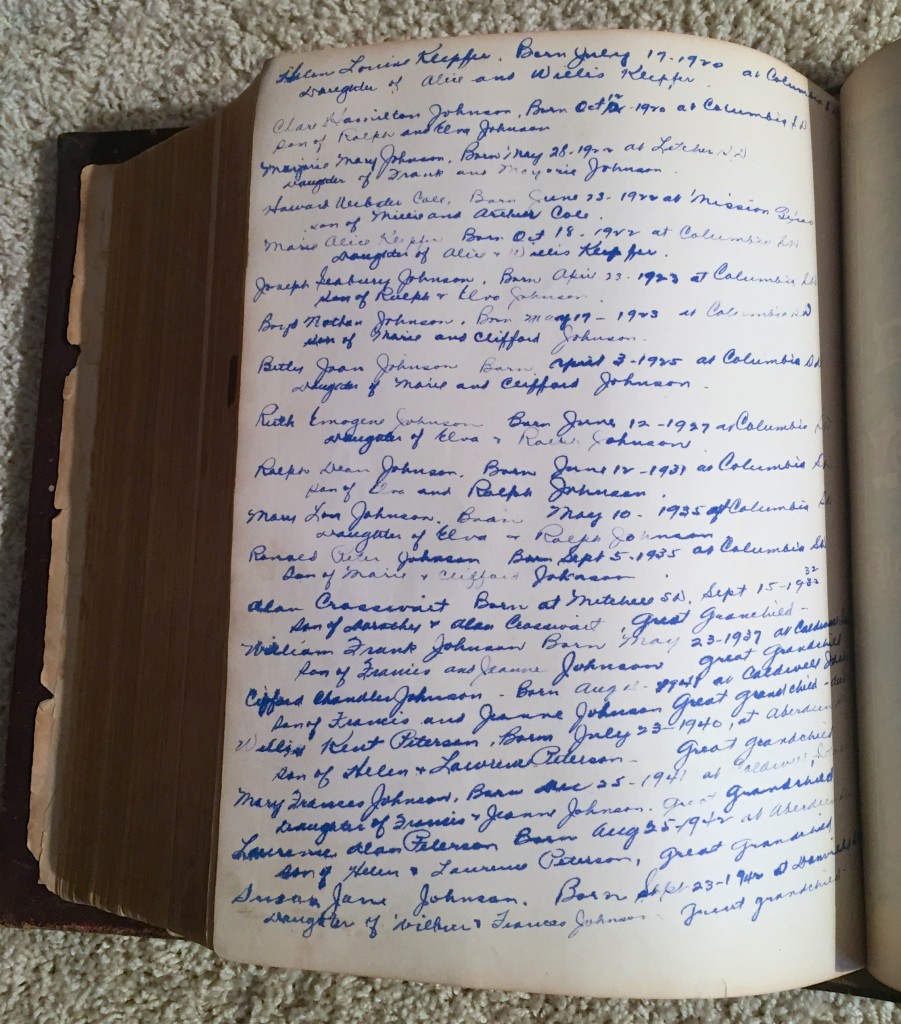

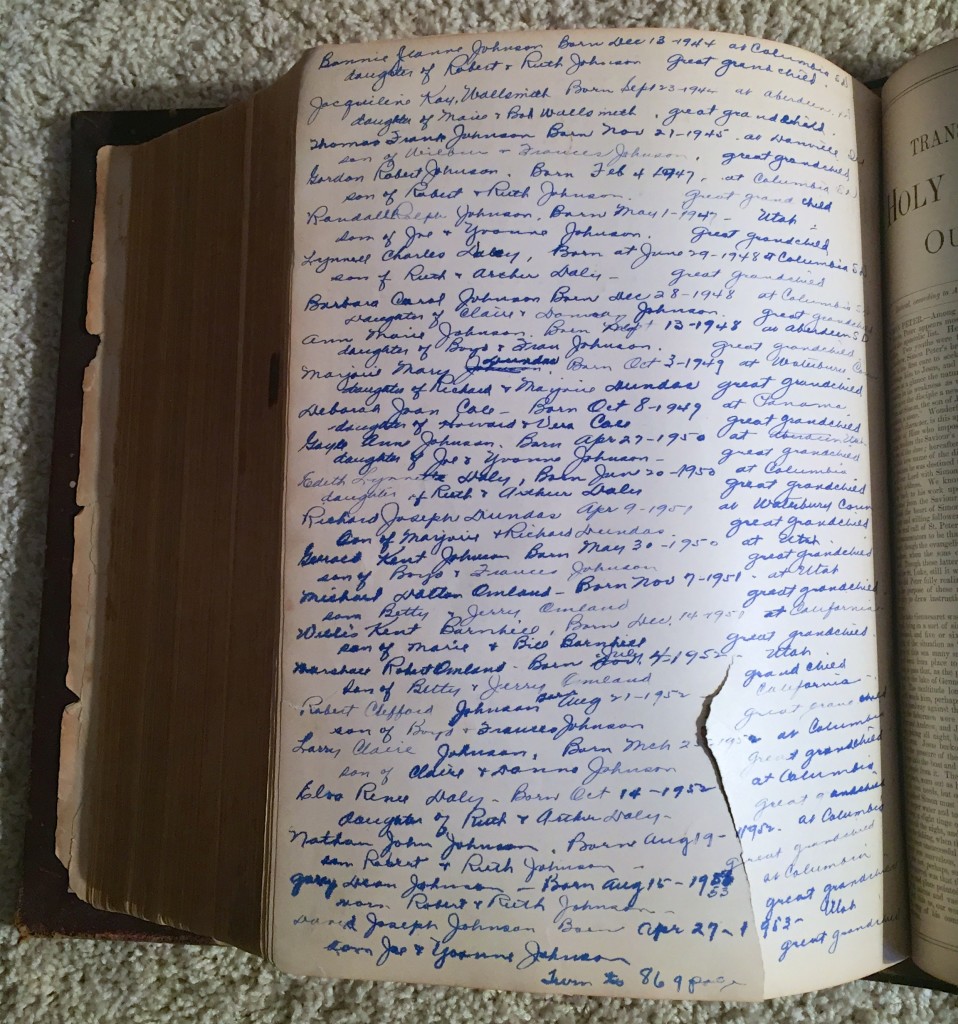

PAGES FROM THE FAMILY BIBLE (gifted to them September 14, 1885):