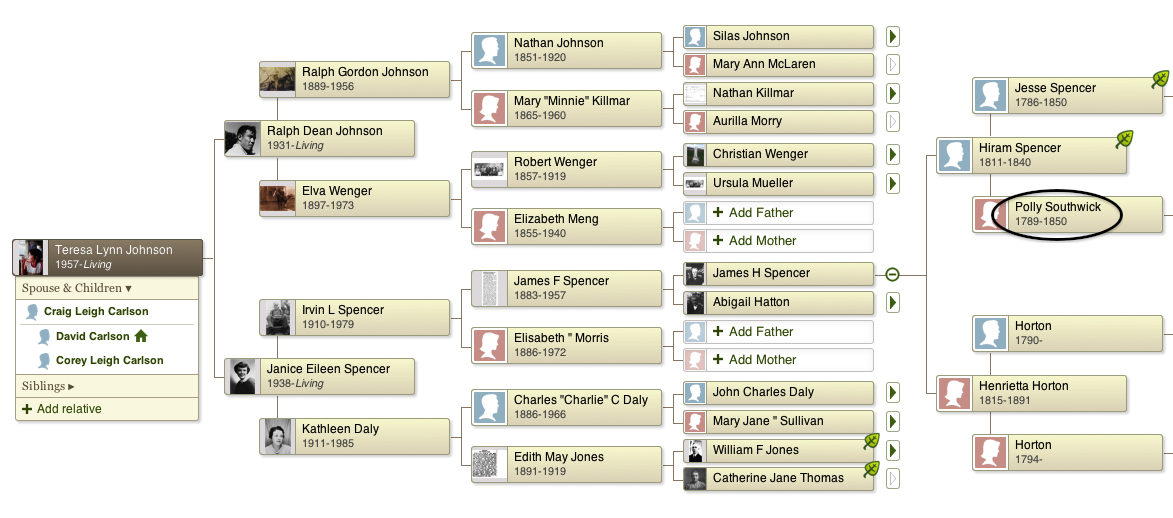

Polly Southwick was born in 1789 to Lemuel Southwick and Mary (Spencer) Southwick. In 1813, at the age of 24, she was married to Jesse Spencer. Jesse and Polly lived in McKean County, Pennsylvania, had five children: Hiram (b. 1811), Elizabeth (b. 1814), Calvin P (b. May 3, 1822), David S (b. 1822), and Daina (b. 1824).

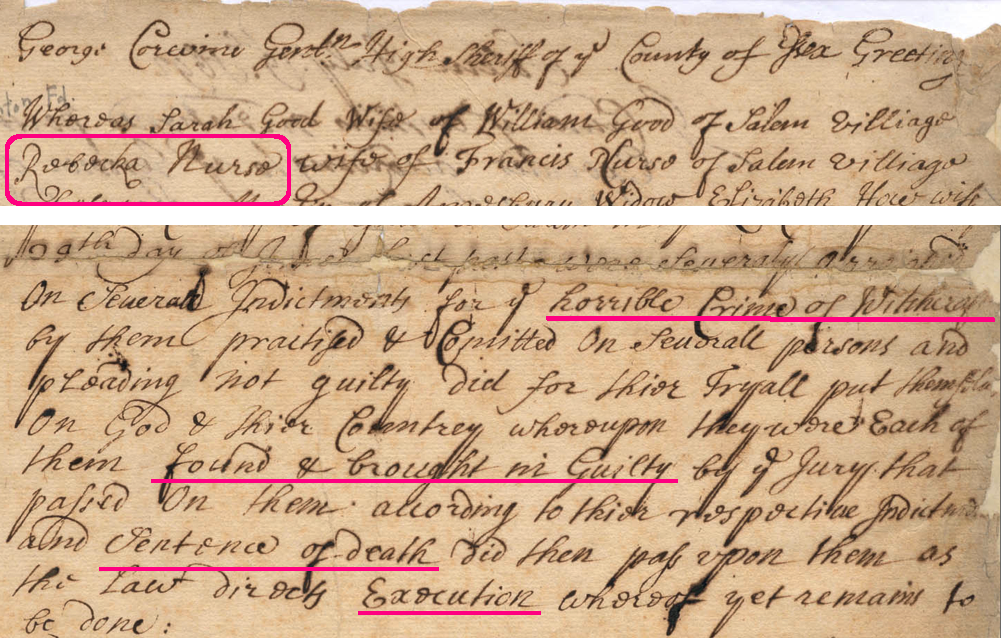

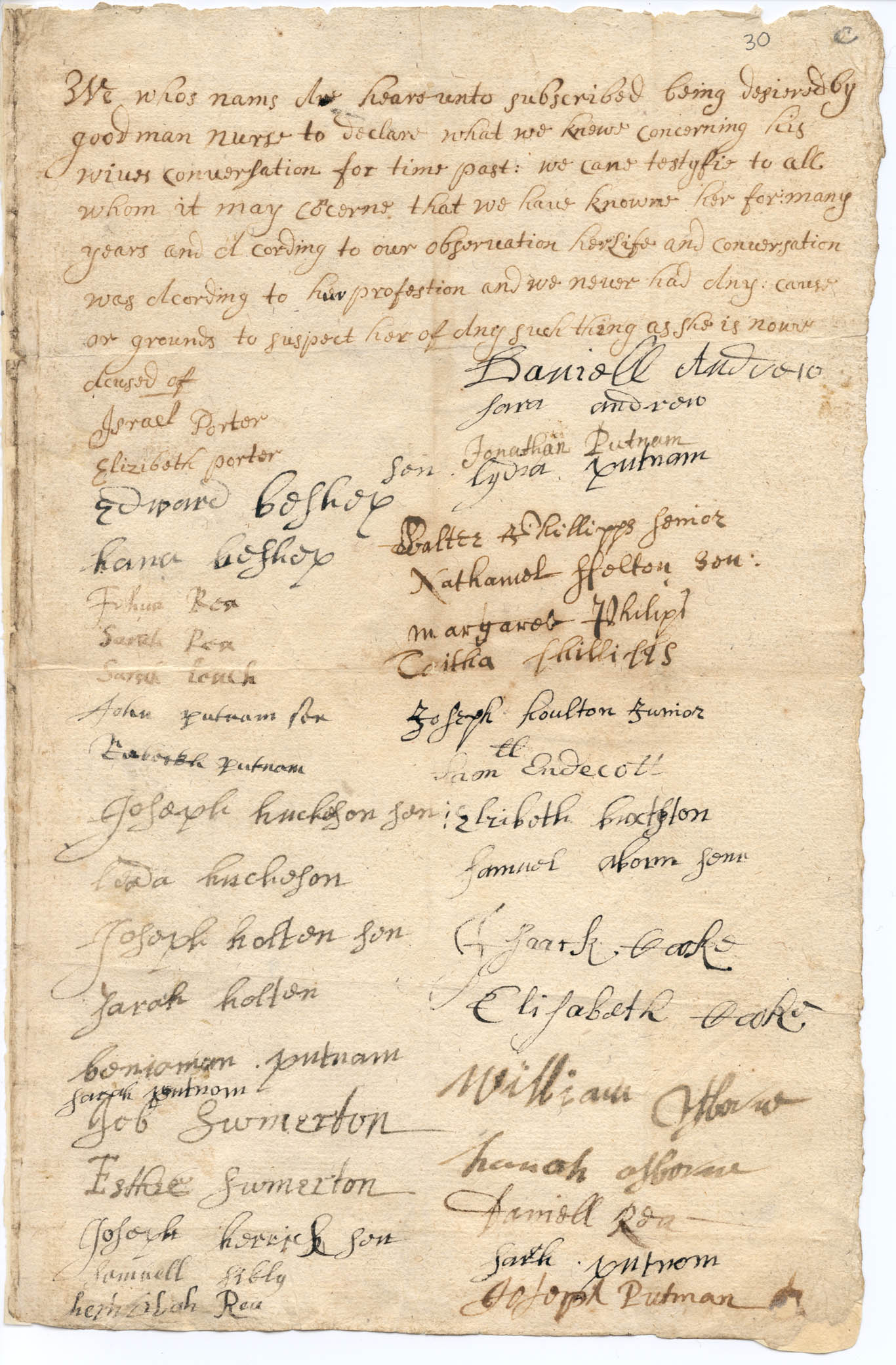

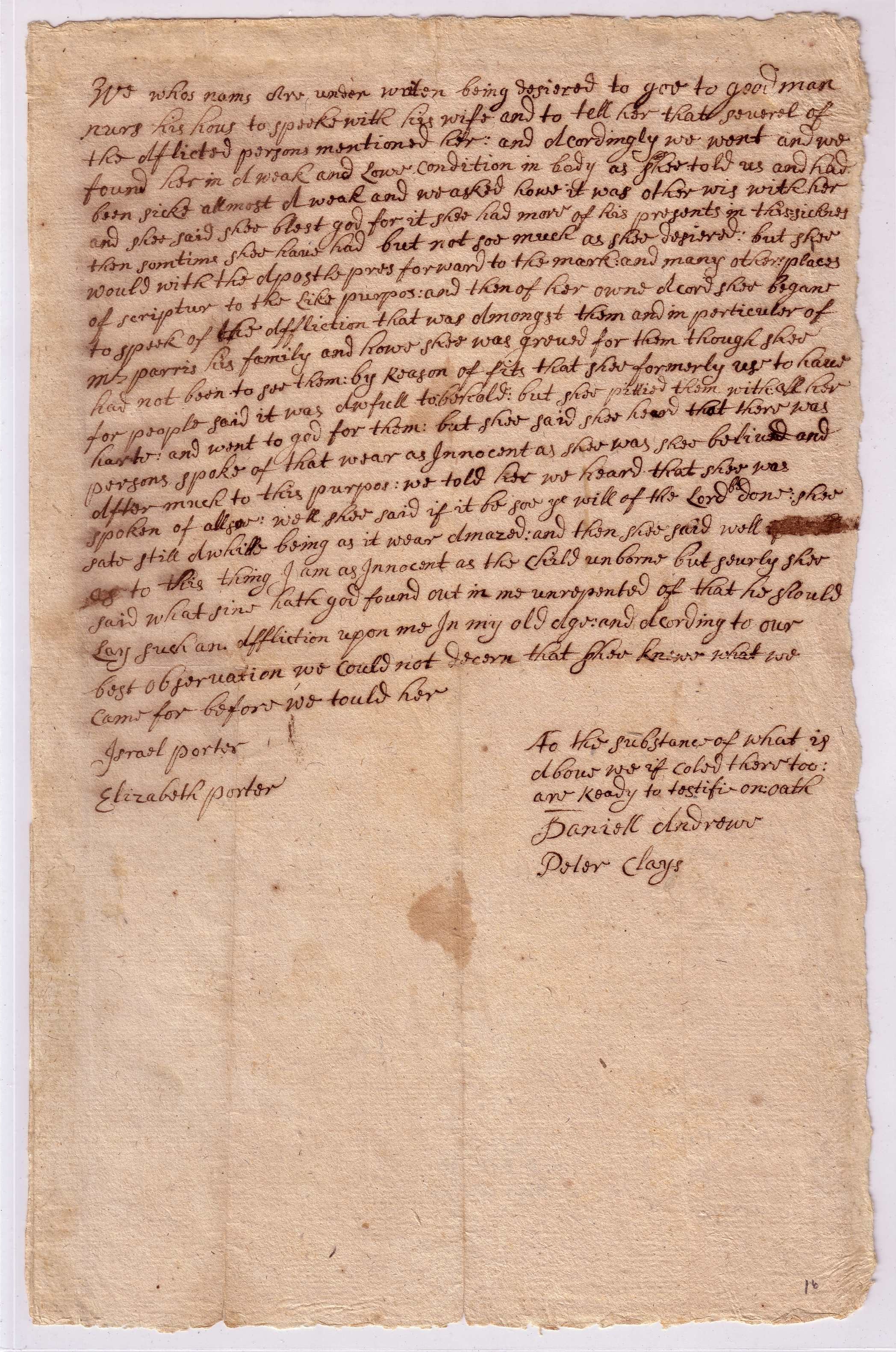

Polly’s paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Dowty, was the great-granddaughter of Rebecca Nurse, one of the 19 people hanged as witches in the Salem witch trials of 1692.

From Ducibel: A Tale of Old Salem by Henry Peterson:

Examination of Rebecca Nurse.

When they arrived at the village, the examination was in progress. Mistress Rebecca Nurse, the mother of a large family; aged, venerable, and bending now a little under the weight of years, was standing as a culprit before the magistrates, who doubtless had often met her in the social gatherings of the neighborhood.

She was guarded by two constables, she who needed no guarding. Around, and as near her as they were allowed to stand, stood her husband and her grown-up sons and daughters.

One of the strangest features of the time, as it strikes the reader of this day, was the peaceful submission to the lawful authorities practised by the husbands and fathers, and grown-up sons and brothers of the women accused. Reaching as the list of alleged witches did in a short time, to between one hundred and fifty and two hundred persons—nearly the whole of them members of the most respectable families—it is wonderful that a determined stand in their behalf was not the result. One hundred resolute men, resolved to sacrifice their lives if need be, would have put a stop to the whole matter. And if there had been even twenty men in Salem, like Joseph Putnam, the thing no doubt would have been done.

And in the opinion of the present writer, such a course would have been far more worthy of praise, than the slavish submission to such outrages as were perpetrated under the names of law, justice and religion. The sons of these men, eighty years later, showed at Lexington and Concord and Bunker Hill, that when Law and Peace become but grotesque masks, under which are hidden the faces of legalized injustice and tyranny, then the time has come for armed revolt and organized resistance.

But such was the darkness and bigotry of the day in respect to religious belief, that the great majority of the people were mentally paralyzed by the accepted faith, so that they were not able in many respects to distinguish light from darkness. When an estimable man or woman was accused of being a witch, for the term was indifferently applied to both sexes, even their own married partners, their own children, had a more or less strong conviction that it might possibly be so. And this made the peculiar horror of it.

In at least fifty cases, the accused confessed that they were witches, and sometimes accused others in turn. This was owing generally to the influence of their relatives, who implored them to confess; for to confess was invariably to be acquitted, or to be let off with simple imprisonment.

But to return to poor Rebecca Nurse, haled without warning from her prosperous, happy home at the Bishop Farm, carried to jail, loaded with chains, and now brought up for the tragic farce of a judicial examination. In this case also, the account given in my friend’s little book is amply confirmed by other records. Mistress Ann Putnam, Abigail Williams (the minister’s niece), Elizabeth Hubbard and Mary Walcott, were the accusers.

“Abigail Williams, have you been hurt by this woman?” said magistrate Hathorne.

“Yes,” replied Abigail. And then Mistress Ann Putnam fell to the floor in a fit; crying out between her violent spasms, that it was Rebecca Nurse who was then afflicting her.

“What do you say to those charges?” The accused replied: “I can say before the eternal Father that I am innocent of any such wicked doings, and God will clear my innocence.”

Then a man named Henry Kenney rose, and said that Mistress Nurse frequently tormented him also; and that even since he had been there that day, he had been seized twice with an amazed condition.

“The villain!” muttered Joseph Putnam to those around him, “if I had him left to me for a time, I would have him in an amazed condition!”

“You are an unbeliever, and everybody knows it, Master Putnam,” said one near him. “But we who are of the godly, know that Satan goes about like a roaring lion, seeking whom he may devour.”

“Quiet there!” said one of the magistrates.

Edward Putnam (another of the brothers) then gave in his evidence, saying that he had seen Mistress Ann Putnam, and the other accusers, grievously tormented again and again, and declaring that Rebecca Nurse was the person who did it.

“These are serious charges, Mistress Nurse,” said Squire Hathorne, “are they true?”

“I have told you that they are false. Why, I was confined to my sick bed at the time it is said they occurred.”

“But did you not send your spectre to torment them?”

“How could I? And I would not if I could.”

Here Mistress Putnam was taken with another fit. Worse than the other, which greatly affected the whole people. Coming to a little, she cried out: “Did you not bring the black man with you? Did you not tell me to tempt God and die? Did you not eat and drink the red blood to your own damnation?”

These words were shrieked out so wildly, that all the people were greatly agitated and murmured against such wickedness. But the prisoner releasing her hand for a moment cried out, “Oh, Lord, help me!”

“Hold her hands,” some cried then, for the afflicted persons seemed to be grievously tormented by her. But her hands being again firmly held by the guards, they seemed comforted.

Then the worthy magistrate Hathorne said, “Do you not see that when your hands are loosed these people are afflicted?”

“The Lord knows,” she answered, “that I have not hurt them.”

“You would do well if you are guilty to confess it; and give glory to God.”

“I have nothing to confess. I am as innocent as an unborn child.”

“Is it not strange that when you are examined, these persons should be afflicted thus?”

“Yes, it is very strange.”

“Do you believe these afflicted persons are bewitched?”

“I surely do think they must be.”

Weary of the proceedings and the excitement, the aged lady allowed her head to droop on one side. Instantly the heads of the accusers were bent the same way.

Abigail Williams cried out, “Set up Mistress Nurse’s neck, our necks will all be broken.” The jailers held up the prisoner’s neck; and the necks of all the accused were instantly made straight again. This was considered a marvelous proof; and produced a wonderful effect upon the magistrates and the people. Mistress Ann Putnam went into such great bodily agony at this time, charging it all upon the prisoner, that the magistrates gave her husband permission to carry her out of the house. Only then, when no longer in the sight of the prisoner, could she regain her peace.

“Mistress Nurse was then recommitted to the jail in Salem, in order to further examination.”

Polly (Southwick) Spencer died in 1850 at the age of 61 in Keating, Pennsylvania.